Video narrated and hosted by Fred Mills. This video and article contain paid promotions from Masterworks.

Antwerp, Belgium, is a place known for art, fashion, and a bustling port that has become the center of the world’s diamond trade.

But it’s not all glitz and glamor here. Just go for a drive and you’ll see why. This picturesque old town has major traffic problems, affecting not only local people and industry, but also the rest of Europe.

But thanks to some incredible underground construction methods, Antwerp is now on track to complete a huge piece of infrastructure it’s been trying to complete for decades.

From a sunken river tunnel to a stacked canal route to a huge new park, take a deep dive into one of Europe’s most important and little-known megaprojects.

Above: The area around the city is becoming one grand building site, producing the most impressive line-up of engineering this country has ever attempted.Image provided by: Lantis

Few European cities are better suited for international trade than Antwerp. It has the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Brussels to the south, and a large ancient body of water known as the North Sea to the west.

Antwerp is home to one of the world’s major ports, with major highways leading to other countries and cities.

All of this flows into one paved road on the outskirts of the city: the Antwerp Ring Road. But driving from point A to point B can be frustrating, as there’s only half the loop right now.

In 2022, drivers spent an average of 61 hours stuck in traffic, due in part to the unfinished ring road. The two current downstream tunnels have become bottlenecks, and traffic congestion has spread to residential areas.

Moreover, the road is also an important element of the trans-European transport network linking Paris and Amsterdam along the North Sea-Mediterranean Corridor.

But things are about to change. Antwerp is finally completing the final jigsaw piece with the wonderfully named Oosterweel Link project. It’s a series of construction jobs that should be simple, but they’re not, they’re a hassle for construction teams and residents, and they’re great material for a construction YouTube channel. .

Above and below: Antwerp ring road before and after the Oosterwheel link was completed.

Much of the challenge here is geography. First of all, there is a river on the way, and it is quite a big river.

In addition to that, completing the ring requires passing through another water obstacle: the Albert Canal.

This is why it is called Belgium’s “project of the century”. First proposed in the mid-1990s, it is currently being developed by Lantis on behalf of the Flemish government.

All in all, this is not just a boring ring road like the M25 in the UK. There are many tunnels built here in a very unusual way.

go underground

First up is the brand new Scheldt Tunnel. This is where his two main sections of the project, on the left and right banks of the river, meet.

This huge tunnel is an important part of completing the ring and assists the driver. cyclist – Dive under the river.

“First of all, we had to excavate a huge construction pit up to 25 meters underground. That meant dewatering the soil and excavating it,” says Yan, project director of the construction consortium TM COTU. Bauens says.

“The moment this construction pit was ready, we were able to start building the actual tunnel. And that’s what we’re building at the moment.”

Above: As well as a six-lane car tunnel with three lanes in each direction, there is also a 6-meter-wide tube dedicated to bicycles.Image provided by: Lantis

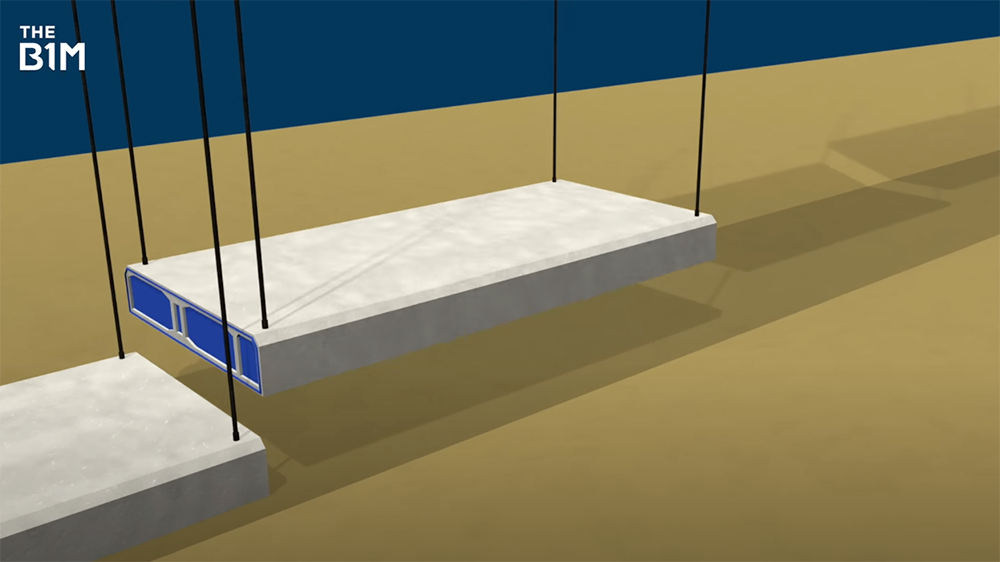

To create the 1,800-meter link, eight giant segments, each weighing around 60,000 tons, would have to come together under water.

First, the team drilled a huge new hole in Zeebrugge, about 100 kilometers from Antwerp, where there was more space. In it, they are constructing eight huge new concrete tunnel segments.

When ready, special seals close the openings at each end. The vast hole fills with water and parts rise to the surface.

Tugboats will then connect and once a suitable weather window opens in mid-2025, each segment will be slowly pulled through 180 kilometers of sea around the coast, through parts of the Netherlands and down to Antwerp.

Upon arrival, each segment will be lowered into a new trench on the ocean floor in accordance with the shipping schedule.

The water between each segment is pumped out, creating a vacuum that draws them together to form a watertight seal.

Once the sealed end of each segment is removed, everything is buried beneath the riverbed and the tunnel is completed.

Above: The Scheldt Tunnel is constructed using the dip tube method.

Construction of this tunnel alone is an enormous procedure that requires an insane level of precision. This dynamic gives great energy to the amazing team tasked with building the tunnel.

“The quality has to be very good. There are a lot of people checking, measuring and making sure that everything is in the right place,” explains Dieter van Parijs, project manager at THV COTU. Did. “Because once the water fills up here at the construction dock, there’s nothing we can do.”

Buried pipe tunnels may not be new, but they typically run in a straight line. It has a fairly pronounced bend, so some segments are built slightly curved.

On the other side of the tunnel is the new Austerweel Junction. Here, traffic briefly appears above ground and either heads to the port or descends into another new tunnel.

Next is the canal tunnel. 2.5 kilometers under the Albert Canal he has four tubes stacked two on top of each other.That is do not have It’s the usual way to build tunnels, but it’s being built this way so drivers can go in one of two directions after merging with the existing ring road.

Another reason it is done this way is to reduce the horizontal space the tunnel takes up in this narrow waterway used by large ships and to provide the necessary depth for ships.

To integrate the existing ring with the new tunnel, a key part of it would have to be demolished: a huge viaduct. What will replace this is a series of more tunnels under the canal and a huge new area covered with parks, cycle paths and walking trails.

Above: Austerweel Junction is embedded into the landscape to make it less visible from a distance.Image provided by: Lantis

But before the viaduct can be removed, a temporary bypass must first be built next to it to maintain traffic while tunneling takes place.

“Underground is also where the old city walls were, so there are a lot of obstacles. We have to build across a canal and we are working next to an existing bridge, so we need to keep traffic flowing. ” said Johan Mignon, Technical Director of TM ROCO.

“On the other hand, we are very close to residential areas. So it’s difficult to keep the public supporting us.”

expensive project

By now, you may be wondering how much all this will cost. In total, the project is expected to generate approximately 7 billion euros in revenue, which at the time of filming was equivalent to approximately 7.6 billion USD.

Most of that money is borrowed from the Flemish government, but the European Investment Bank has so far put in 500 million euros. The money will be repaid with express charges.

Overall, a lot has happened in the city since construction began in 2018, but there is still much to be done to reach the 2030 completion goal.

Why 2030? Because Oosterweel is just one part of a larger effort to increase green transportation options and make it safer and more accessible across our metropolitan areas. .

Cleverly named Route Plan 2030, the plan’s goal is to reduce the proportion of car travel in the city from 70% to 50%.

The rest will be done by more sustainable means, such as public transport, bicycles, electric scooters, and walking.

Above: Route Plan 2030 aims to reduce people’s reliance on car travel and prioritize environmentally friendly alternatives such as trams.

One of the major buildings built for Oosterweel was a huge new park and ride where people could ditch their cars and hop on a tram heading into the city centre.

All very positive things, but the project dates back to 1996 when it was first proposed. Why did it take so long? Well, the short answer is that it took more than 10 years to decide which method to use.

Previous plans had called for a bridge to replace the canal tunnel. At 1.5 kilometers long and 150 meters high, the bridge would have been truly gigantic.

Many companies supported the idea, but the people of Antwerp did not. In 2009, the people chose not to support the proposal in a referendum.

There were concerns about the environmental impact of a new major road being built near homes, and some felt the idea was being pushed by the city of Brussels.

The name Langewapper may have also turned people off. For those not familiar with Flemish folklore, it refers to a giant who towers over the people of Antwerp and torments them. It’s a somewhat unusual choice.

Above: Architectural model of the Lange Wapper Bridge. Image courtesy of Wwuyts/CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED.

However, after years of debate and consultation, the government of Flanders (the region of Belgium where Antwerp is located) finally approved the plan in 2014, which is currently underway.

It may have taken a long time to move forward, and there is significant engineering ahead to say the least, but we can now see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Completing a project like this has never been easy, but thanks to some great engineering, the city is now finally finishing what it started nearly 30 years ago.

This video and article contain paid promotions from Masterworks. You can skip the waiting list. here.

Video narrated and hosted by Fred Mills. Additional footage and images provided: Lantis, ATV, European Commission, Raja Imran Khan, Roger Price / CC BY-NV-SA 2.0 AgreementSony, Weitz / CC BY-SA 3.0 Certificate and XKP visual engineer.

We welcome you to share content to inspire others, but please be kind. Please play by our rules.