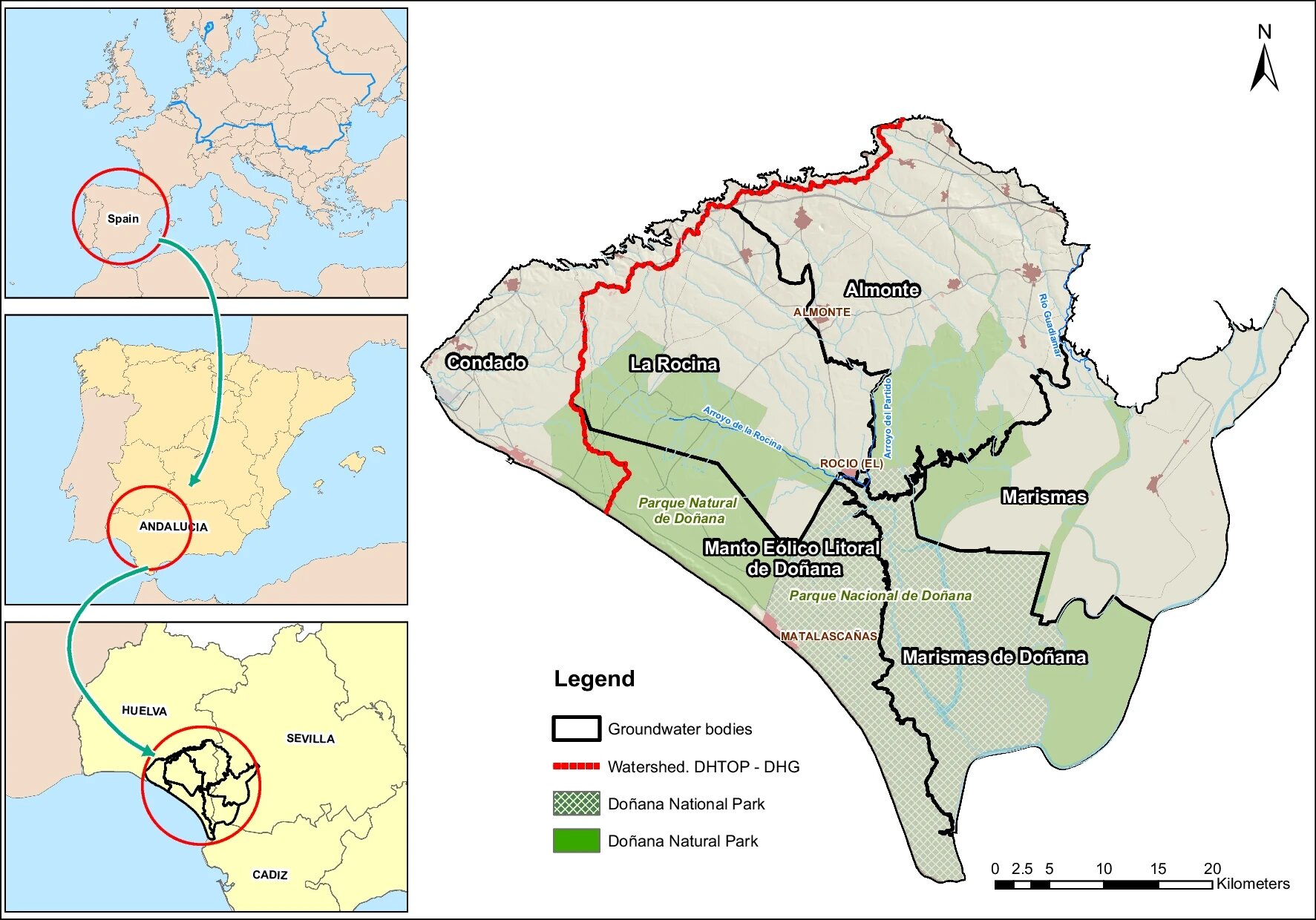

The underlying Almonte Marismas aquifer system of Doñana, the division between six groundwater bodies, and the protected areas within the Doñana National Park and Natural Park (which together constitute the “Doñana Natural Space”) . credit: wetland (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s13157-023-01769-1

× close

The underlying Almonte Marismas aquifer system of Doñana, the division between six groundwater bodies, and the protected areas within the Doñana National Park and Natural Park (which together constitute the “Doñana Natural Space”) . credit: wetland (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s13157-023-01769-1

A team led by the Spanish National Research Council’s Doñana Biological Station and Institute of Geology and Mines investigated more than 70 studies related to groundwater and the conservation status of Doñana in southern Spain, one of Europe’s most emblematic wetlands. did.

This study shows that there is sufficient scientific evidence of the serious impacts caused by groundwater pumping. A total of 22 researchers from different institutions in both the fields of wetland ecology and hydrogeology, with extensive experience in research projects in Doñana, participated in this study.

Data from the Guadalquivir Union (Guadalquivir River Basin Authority) show that over the past 30 years there has been a general decline in groundwater tables across protected areas, especially in areas closest to areas where water is extracted for agricultural and urban uses. It is shown that there is. Additionally, many scientific studies have documented Doñana’s impact on aquatic and terrestrial habitats and water quality.

“Since the 1970s, various scientists and engineers have reported that uncontrolled groundwater pumping would have very serious consequences for Doñana,” says Carolina Guardiola Alberto, CSIC researcher at the Institute of Geology and Mines. . “Our impression is that water and land managers involved in Doñana at various levels either did not heed these warnings or did not take effective action.”

Despite the scientific evidence, for many years no measures have been taken to successfully avoid, or at least mitigate, these impacts on protected areas. Given the regime’s inaction in this regard, the Court of Justice of the European Union found Spain guilty in 2021.

A year later, the European Union will issue a new ruling against Spain unless it quickly agrees to withdraw a bill submitted to the Andalusian regional parliament to expand irrigation around Doñana. warned again.

“While the actions of the European Court of Justice have led to a change in attitude, it remains to be seen whether the necessary measures will be implemented and, above all, whether all relevant authorities and agents will work together to effectively implement these measures. “We remain skeptical that it can be done,” explains the scientist.

Impact on both aquatic and terrestrial habitats

The scientific evidence on the impact of agriculture on doñanas is clear and abundant. Several studies have shown how declining groundwater levels have led to the disappearance of many ponds, which are key to the conservation of many species. One of the reviewed studies, published in 2001, detected that the water table fell by up to 20 meters between 1972 and 1992.

The researchers also noted the disappearance of ponds recorded on historical maps, particularly in northern regions most affected by groundwater depletion, primarily due to irrigation. More recently, in a study published last year, the Doñana Biological Observatory confirmed that almost 60% of the ponds that existed in the 1980s have disappeared.

Additionally, most of the new ponds will flood less frequently than expected based purely on climate change and will dry up sooner than expected, especially in the areas closest to Matarascañas and greenhouses, where the effects of aquifer overexploitation are greatest. There was found. This affects not only aquatic plants but also many animal species that depend on these ponds.

Extraction of water from aquifers also has a major impact on wetlands. With rainfall, surface water flows into wetlands from aquifers. However, these numbers have been on the decline in recent years. Several studies conducted in the Rosina region in the early 2000s suggested a 60% reduction in groundwater discharge to the rivers that circulate through the region. This trend has since been further exacerbated by the significant expansion of intensive agriculture in the region.

Furthermore, reduced groundwater discharge explains changes in the dominant species of riparian forests, with the gradual decline of highly water-dependent willows and the increase of less water-demanding ash trees. .

This problem doesn’t just affect aquatic habitats. It also affects land plants. In Doñana, for example, cork oak trees that are hundreds of years old are now rapidly dying. According to ICTS-RBD data, 8% have already died since 2009, and many are losing their leaves due to falling water tables.

Many other vegetation changes have also been recorded. Species such as Erica scoparia, a type of heather, are being replaced by more drought-tolerant species such as Ulex australis. Additionally, recent studies have documented the establishment of pines and shrubs in many dry temporary pond basins, confirming wetland degradation and loss.

Impact on water quality

Groundwater-dependent agriculture has serious impacts not only on terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity, but also on water quality.

“We tend to think more about water quantity than water quality, but in reality they are just as important,” explains Andy J. Green, CSIC Research Professor at the Doñana Biological Station. “With agricultural and urban expansion, the loading of nutrients and pollutants on wetlands is increasing, especially around El Rocio.” Studies have been conducted in both surface and groundwater.

Impacts on water quality are closely related to the use of pesticides on irrigated red fruit crops (including strawberries). As the flow rate decreases, the concentration of pollutants further increases due to higher evaporation rates, increasing salinity.

Climate change, with rapidly rising temperatures, is promoting the growth of toxic algae and invasive plants under high concentrations of nutrients. For example, phosphorus loading has increased rapidly since 2000, resulting in the expansion of the invasive aquatic fern Azolla filiculoides into wetlands and some ponds, negatively impacting amphibians and aquatic plants.

Recent data shows that nutrient loads in rivers affected by groundwater extraction for agriculture are very high. “We’ve turned national parks into green filters to purify river water that is toxic to fish and other wildlife,” says Andy J. Green.

Contamination of the Doñana aquifer by agricultural and urban activities dates back to the first irrigation expansion in the 1970s, and deteriorating groundwater quality has been recognized by international organizations. “Measures are urgently needed to reduce fertilizer inputs to aquifers and purify water before it enters national parks,” the researchers say.

One of the most frequently heard suggestions when talking about implementing conservation measures in Doñana is to transfer water from other nearby watersheds. However, the scientific team believes this may be unrealistic given the limited amount of surface water available and climate model predictions for southern Spain.

Additionally, surface water supplies from other basins may promote bioinvasion and further eutrophication associated with the expansion of irrigated crops, as has already been seen in the Mar Menor wetlands of southeastern Spain. .

“Thanks to the results of the scientific research carried out in Doñana, it is now possible to explain the relationship between the current state of protected areas and the influence of external factors acting on them, such as direct human actions and climate influences. It changes,” explains Carolina Guardiola. “This knowledge provides the basis for determining measures to protect and restore these ecosystems.”

The paper will be published in a magazine wetland.

For more information:

Andy J. Green and others report that groundwater pumping is causing severe ecological damage to Spain’s Doñana World Heritage Site. wetland (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s13157-023-01769-1