The mid-2000s saw a dramatic shift in the dynamics of European football, as the once-dominant Italian clubs as a whole began to lose their crown. A combination of an aging team, the infamous Calciopoli scandal that tarnished the league’s once-glorious reputation, and the subsequent ouster of Juventus, Fiorentina and Lazio, the best teams in the country at the time.

Going into the 2006 World Cup, the defending champions and favorites were Brazil. Germany, coached by Joachim Loew, were also struggling to win the title on home soil, while England and France each fielded formidable teams into the tournament. Italy was no longer the footballing powerhouse it once was and needed a fresh start, away from all the controversy at domestic level. They needed to showcase their talent on the biggest stage to prove themselves as one of the best soccer nations in the world. A fourth World Cup victory would certainly solidify this claim.

Italians have a rich history of great managers, and some of the greatest tactical developments have come from Italian managers. Marcelo Lippi is definitely among them. Lippi was appointed to turn Italy’s fortunes around after a disappointing 2004 season under manager Giovanni Trapattoni. He believed in rotating his system around his best players while balancing them with utility players who could fill a variety of roles.

BBehind that philosophy, Lippi was keen to foster relationships between players within a structured framework, ensuring fluid movement and strong structural cohesion. This approach made his team fun to watch while winning numerous trophies throughout his career. He combined flair with a control-oriented approach.

Photo: My Greatest Eleven

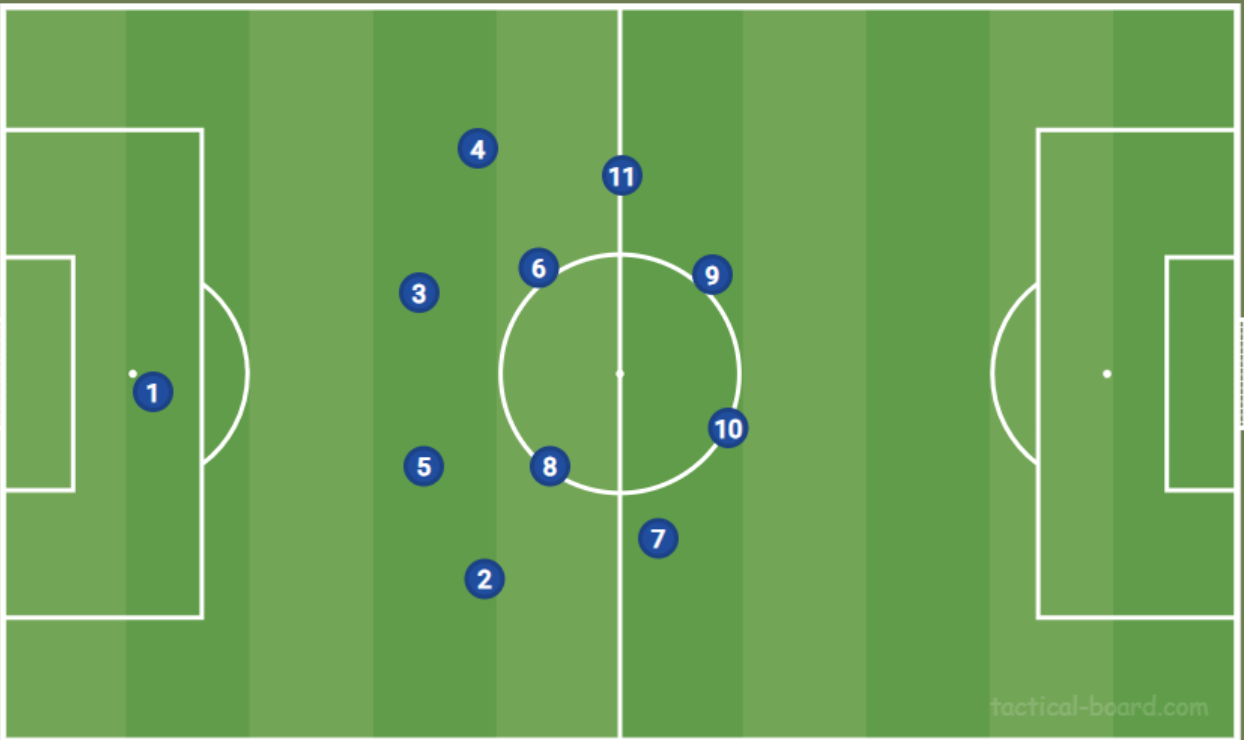

Lippi instructed his team to sit in an attacking 4-4-2 midblock and implement a man-marking system, looking for press traps and triggers all over the pitch. To compensate for this, the two strikers will often be in narrow positions, closing the path to central midfield and forcing the ball into wide or long balls. This was very effective at the 2006 World Cup, as the team found it difficult to bypass the first stages of the build-up against Italy.

This system was certainly similar to Diego Simeone’s 2020/21 Atlético Madrid team in its resting defensive form and the way it disrupted forward ability in the middle. When the opponent shifted the ball wide, the wingers actively tried to close down the full-backs and force them into errors. However, the core of this strategy was to form a 4-3-3 pressing shape to control space high up the field and limit the opposition’s passing options.

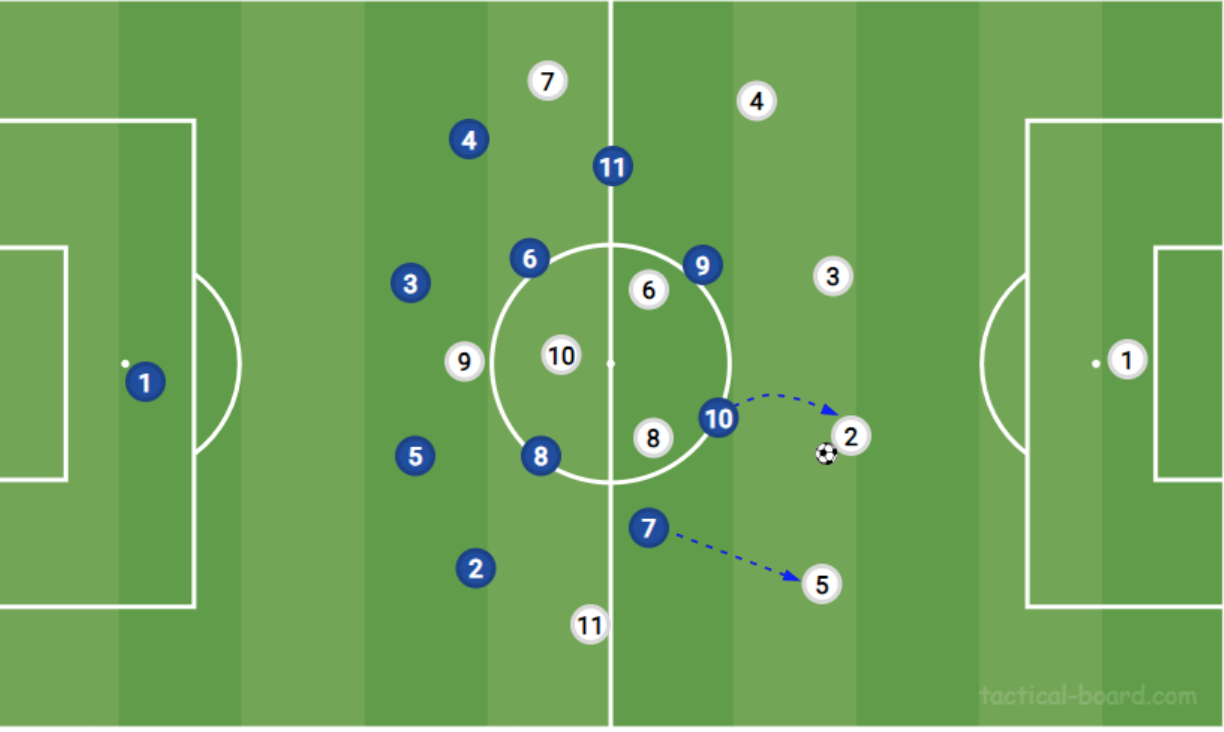

When the front line breaks down, the standard man-marking system kicks in and they immediately try to steal the ball. Deficiencies in this usually result in players being dragged out of their positions or other players being sent off to fill the gaps created.

Once they regain possession, Italy will try to pin their opponents on the flanks and mount a counter-attack. When this team is overloaded, they shift the play by moving the ball into the middle, focusing on overloading the central spaces and exploiting the spaces between the opposition lines in a very fast and direct manner. . This often leaves spaces wide for onrushing full-backs or wingers.

If the ball is lost, an aggressive man-to-man counterpress is activated to win the ball as high as possible and restart the attack.

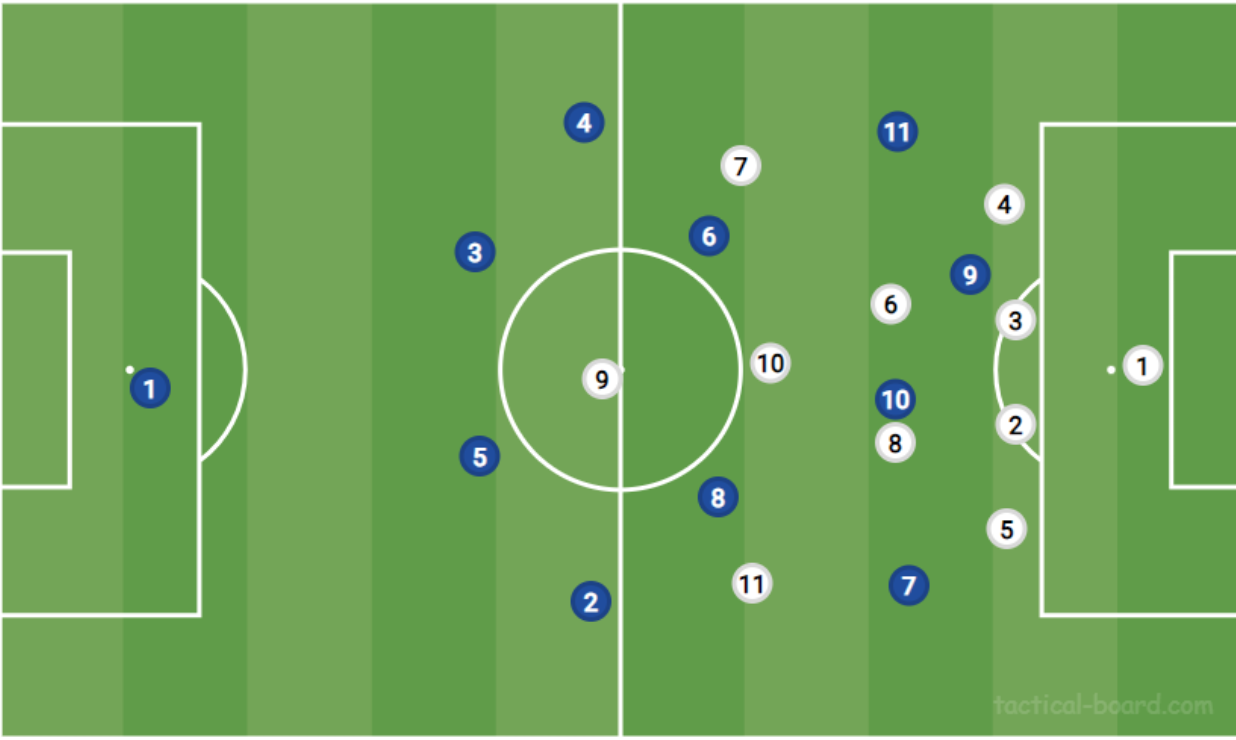

It was clear that Lippi’s attack structure was clearly vertical. In a very Sarriball style, Italy will try to find vertical solutions to the opponent’s press. Vertical in nature, they often sought to stretch out the opponent’s midfield and defensive lines to create space between the lines.

Starting from the back, the keeper could play a simple pass to one of the two centre-backs, or the full-back could drop back and receive the ball. From there, the aim was to transfer the ball to either Andrea Pirlo or Gennaro Gattuso in the middle. Although Gattuso was technically more than capable, it was Pirlo who assumed the role of deep playmaker, or “register” as he is commonly called.

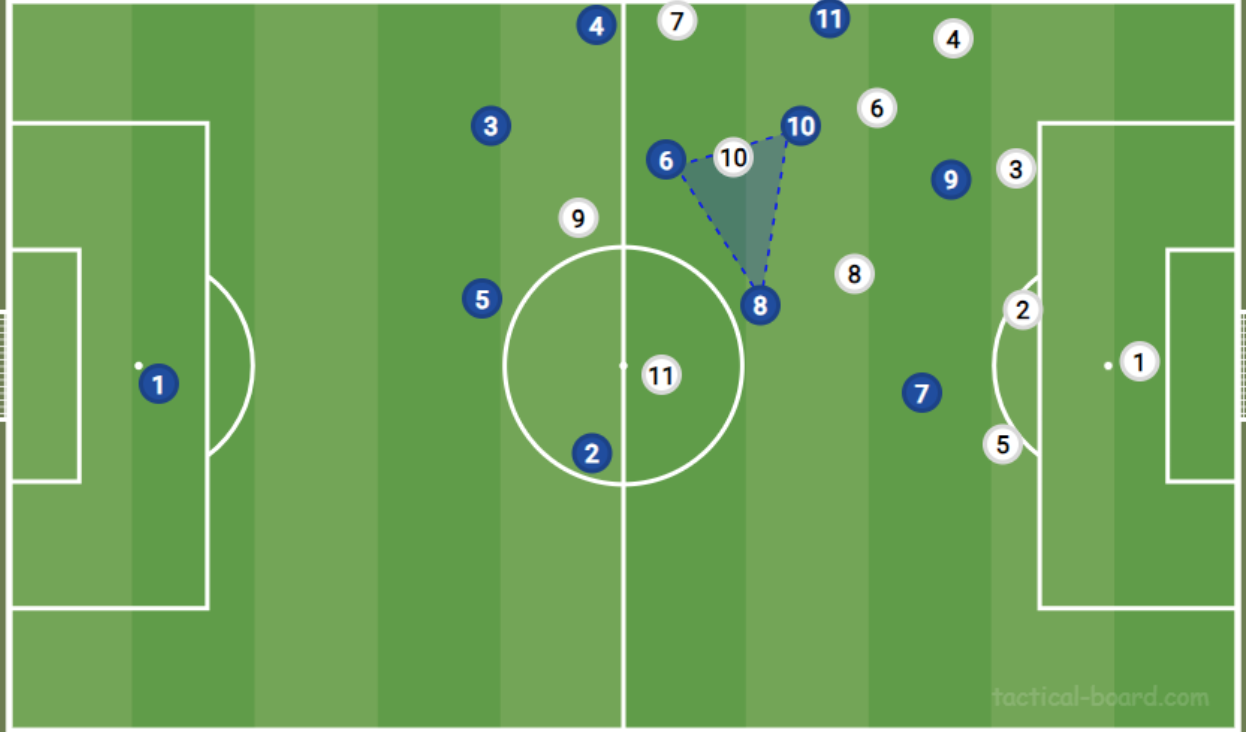

Gattuso could instead aim to move up higher and take up the space between the lines, as Francesco Totti also dropped deeper into the half-spaces from his No. 10 role, looking to receive between the lines. , a 4-3-3 formation was born, resulting in overload. Pitch side during build-up.

Gattuso’s ability to move forward with the ball allowed for a fluid midfield, with players having the option to stay deep and receive. The vertical extension of the outfield also allows two wingers to move into the half-spaces, adding further confusion to the defense and providing additional attacking options. Luca Toni, on the other hand, occupied the centre-backs by staying close to one of them or running into the channels when space became available behind the defensive line, giving him a more unpredictable edge in attack.

Lippi’s flexible and fluid tactical approach was the springboard for Italy to reach the World Cup finals, and despite their dominant defence, he adopted a much more attacking approach than his predecessor. was praised. This newfound talent and dynamism took Italy to the very pinnacle of world football as they won the World Cup final in Berlin, drawing France 1-1 in regular time before defeating them 5-3 on penalties. He reaffirmed his position and won his fourth championship. Win the title on the biggest stage in the game.

Posted by: Arhum Siddiqui / @MrArhumSiddiqui

Featured image: @GabFoligno / Simon M. Bluti / Getty Images