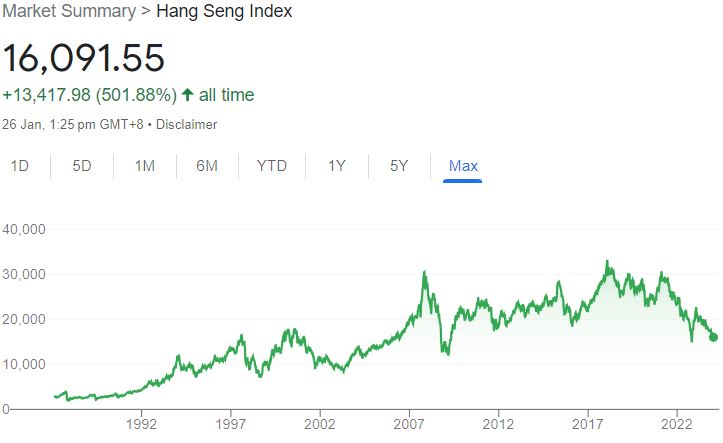

Taipei, Taiwan – Like many Hongkongers, accountant Edelweiss Lam watched the city’s stock market erase 14 months of gains last week as the Hang Seng Index fell below the psychological benchmark of 15,000 points.

This wasn’t the first time Lam, who has been investing in Hong Kong stocks off and on since the late 1990s, has seen something like this happen.

The index fell below 15,000 points during SARS in 2003, the global financial crisis in 2008, and the coronavirus zero lockdown in 2022.

But Lam said that while ups and downs are part of the investment game, it felt different this time to see the Hong Kong stock market go “back to square one”, a key indicator of declines.

“I don’t think I can see the future,” Lam told Al Jazeera by phone from Hong Kong.

Lam said the reason lies in China.

As the Chinese government tightens its control over all aspects of Hong Kong life, including the economy, and pessimism remains about China’s post-pandemic recovery, investors are voting with their money and looking to other markets. I’m aiming.

More than a quarter of a century after Hong Kong was handed back to China, Hang Seng has more or less returned to the state it was in its last days as a British colony.

On Friday, the index remained below 16,100 points, lower than it was on the handover date of July 1, 1997.

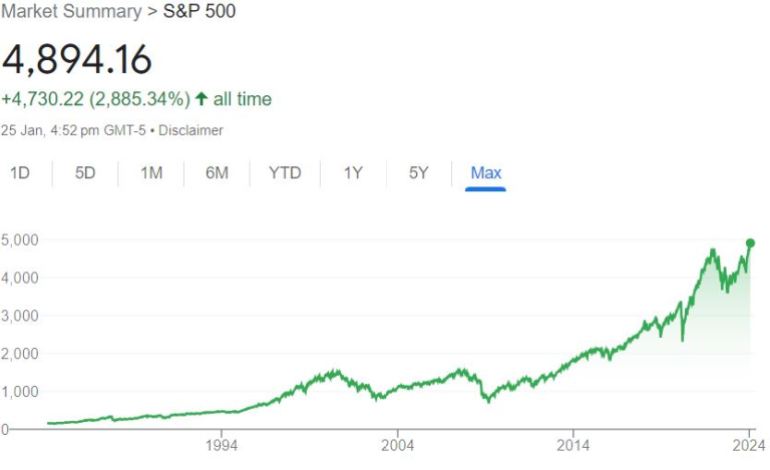

During the same period, stocks in the US, Japan, and other popular markets boomed.

Investor money in the SP500, the most popular measure of U.S. market performance, has increased nearly 10 times since 1997.

Mr. Lam, whose investment portfolio includes blue-chip stocks, term deposits, and real estate, said, “If there are new announcements from the Chinese government regarding regulations or regulation of some industries, the market could fluctuate significantly.” Ta.

“The relationship between Hong Kong and China is becoming closer and more tightly controlled, so we can’t ignore what Hong Kong is doing in China.”

Hong Kong has been at the forefront of China’s crackdown in recent years, from imposing strict national security laws to tightening regulations on giant companies such as Alibaba and Tencent and raiding foreign companies on the mainland.

Many of China’s biggest companies are dual-listed in Hong Kong and China, and together with Chinese banks and other tech companies, make up a large portion of the Hang Seng Index.

At the same time, the Chinese economy is facing troubling structural problems such as a declining population, large local government debts, and a slow-moving real estate crisis, as well as the effects of the new coronavirus infection (COVID-19) and the severe pandemic caused by the Chinese government. Struggling to recover from restrictions.

Gross domestic product (GDP) will officially grow 5.2% in 2023, the weakest performance in decades, excluding the pandemic.

Despite Beijing’s insistence that China is open for business, foreign investors’ confidence is waning.

Last year, China recorded the first decline in foreign direct investment in 12 years, with inflows down 8% to $157.1 billion.

“If you look at the broader confidence in the financial sector and the broader economy, first of all, the economic fundamentals in Hong Kong and China are not very strong at the moment,” said Chim Li, China analyst at the newspaper. The Economic Information Department told Al Jazeera.

Mr Li said China’s achievement of its economic growth targets last year was “not particularly impressive” as the country had set relatively weak targets.

Analysts estimate that about $6 trillion, more than a quarter of the total U.S. economy’s output, has disappeared from Chinese and Hong Kong stock markets since the beginning of 2021.

China’s CSI300 index, which covers the top 300 companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges, has fallen more than 40% in the past three years, and the Hang Seng Index has fallen 50% over the same period, according to Bloomberg data.

Investors are instead flocking to other markets such as Japan and the United States, where analysts are predicting a bullish 2024.

The Nikkei 255 index, an index of top companies on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, hit a high last week not seen in more than 30 years, and on Thursday, New York’s S&P 500 index traded at its highest level for six consecutive days. finished.

“[Hong Kong’s] While the economy may now be just a big rounding error in China’s GDP, it still plays a key role in financial and capital market transactions with mainland China. So it’s axiomatic that bearish sentiment and stock price declines in China are well under way. [Hong Kong] George Magnus, an assistant at Oxford University’s China Center and a SOAS researcher in London, told Al Jazeera.

The decline in Hong Kong’s rights and freedoms, which were supposed to be guaranteed until 2047 under the agreement known as “one country, two systems,” has fueled a crisis of trust.

Since the national security law was passed in 2020, opposition groups and independent media in the city have been largely wiped out, and hundreds of people have been arrested for non-violent crimes related to their activism and speech.

Hundreds of thousands of Hongkongers have left Hong Kong, along with their funds, as Beijing tightens control.

Last year, Lam decided to move his pension fund overseas and said he intended to sell his remaining stock investments in Hong Kong at a loss.

Regarding the government’s economic policies, Lam said, “They say they want to do something, but we haven’t seen any actual action.”

Hong Kong lowered stamp duty on property sales and stock transfers in October, but consumption and tourism have yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels.

Analysts say bolder action will be needed to revive the economies of both Hong Kong and China.

Bloomberg reported this week, citing sources, that the Chinese government is considering a $278 billion stock market rescue plan, but many analysts believe broader structural reforms are needed to restore investor confidence. argues that it is necessary.

A similar rescue plan rolled out after China’s stock market crash in 2015 had mixed results, even though the government moved quickly and the overall economy was on stronger fundamentals.

Alicia García Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis, said memories of the rescue plan and fears that Beijing would not implement difficult but necessary reforms have contributed to the muted response to the plan. He said it was one of the reasons.

“The market is just saying, Sorry it’s not growing. I don’t trust your numbers. “Your future looks bleak. That wasn’t the case in 2015. At one point. I think this is the first difference because people thought it was a shock,” García Herrero told Al Jazeera.

Beijing likely has less room for maneuver this time around, due to its high debt levels and limited scope for monetary easing.

“They used so many bullets that the next one is less reliable,” she said.