The violins, violas and cellos played by the Ocean Orchestra in its debut performance at Milan’s famous Teatro alla Scala on Monday contain stories of despair and redemption.

The wood bent, carved and gouged to form the instruments was salvaged from a dilapidated smuggler ship that carried migrants to the Italian coast. The luthier who created these is an inmate in Italy’s largest prison.

The project, named “Metamorphosis,” focuses on transforming things that could otherwise be discarded into something of value to society, based on the principle of rehabilitation. Rotten wood becomes high-end musical instruments, and inmates become craftsmen.

The two inmates were given permission to watch a concert in which 14 prison-made stringed instruments played a program that included works by Bach and Vivaldi. They sat in the Royal Box alongside Mayor Giuseppe Sala.

“I feel like Cinderella,” Claudio Ramponi said as a friend approached him in the lobby before the show, wearing a bow tie to complement his new suit. “This morning I woke up in an ugly, dark place. Now I’m here.”

Far from the majestic La Scala Opera House, the Opera Prison on the southern edge of Milan houses more than 1,400 prisoners, including 101 Mafia members, who are held in strict regimes of near-total isolation. Masu.

Other prisoners, like Nicolae, who joined Lamponi at La Scala, are given more freedom. Since joining the prison’s musical instrument workshop in 2020, Nicolae, who refuses to give his full name and prefers to make light of the charges that landed him in prison 10 years ago, has been making music from crude instruments made from plywood. He graduated to a harmonious instrument and became a master of opera. A violin suitable for the stage of La Scala.

“That’s how I began to interact with trees,” Nicolae said recently in a prison workshop filled with the smell of wood shavings and the faint sound of a jigsaw, amid rows of chisels. They realized I was handy. ”

He said working with an instrument for four to five hours a day gives him a sense of peace to reflect on “the mistakes I made” and the skills to think about the future. “I’m gaining self-esteem,” he said, “and that’s no small thing.”

One of the prison workshop’s “graduates” has completed his sentence and is working as a master luthier in another prison in Rome.

“I hope that someday I can recover like this violinist,” Nicolae said.

For another prisoner, who requested anonymity, making instruments is a form of physical and psychological therapy. He requested anonymity because he fought two wars in his homeland, where he served as a political prisoner and said he was beaten so much that he needed crutches to walk.

As he gently carves the back of the violin’s top, measuring its thickness with the instrument to achieve perfect pitch, he falls into a trance. If he digs too deep he’ll be back to square one. Through his own arduous journey to a new country, one could understand his desperation that drove his emigrants onto unseaworthy ships.

“When I work on these pieces, I think about the refugees and women and children that this tree has carried. As I work, I think about what this tree has lived through, and that’s all I can think about. I’m thinking about it,” he said.

Ramponi and fellow inmate Andrea Volonghi found a new purpose for their life sentences, tearing apart a smuggler’s boat placed in the yard between prison sections. Initially, the boats were converted into crosses and nativity scenes, but the inmates, who were already trained as luthiers, thought why not turn them into musical instruments?

So they are currently searching for key parts to use in their instrument workshop, removing rusty nails in the process. The more damaged wood is sent to another prison in Rome, where prisoners make rosary crosses. At the moment when it comes full circle, immigrants assemble rosaries in a Vatican workshop.

The boat arrived at the Opera House still in its possession, but inside it still contained remnants of the lives of the migrants, who the United Nations said had died or gone missing on the perilous Central Mediterranean crossing since 2014. It is also a reminder of the 22,870 immigrants living in the country.

A shoulder bag containing diapers, baby bottles and shoes for toddlers sits on one bow, along with canned Tunisian anchovies and tuna and a number of plastic sandals.

“I don’t know what happened to them, but I hope they survive,” Vorongi said, thinking of a pair of small pink sneakers with the familiar Western logo.

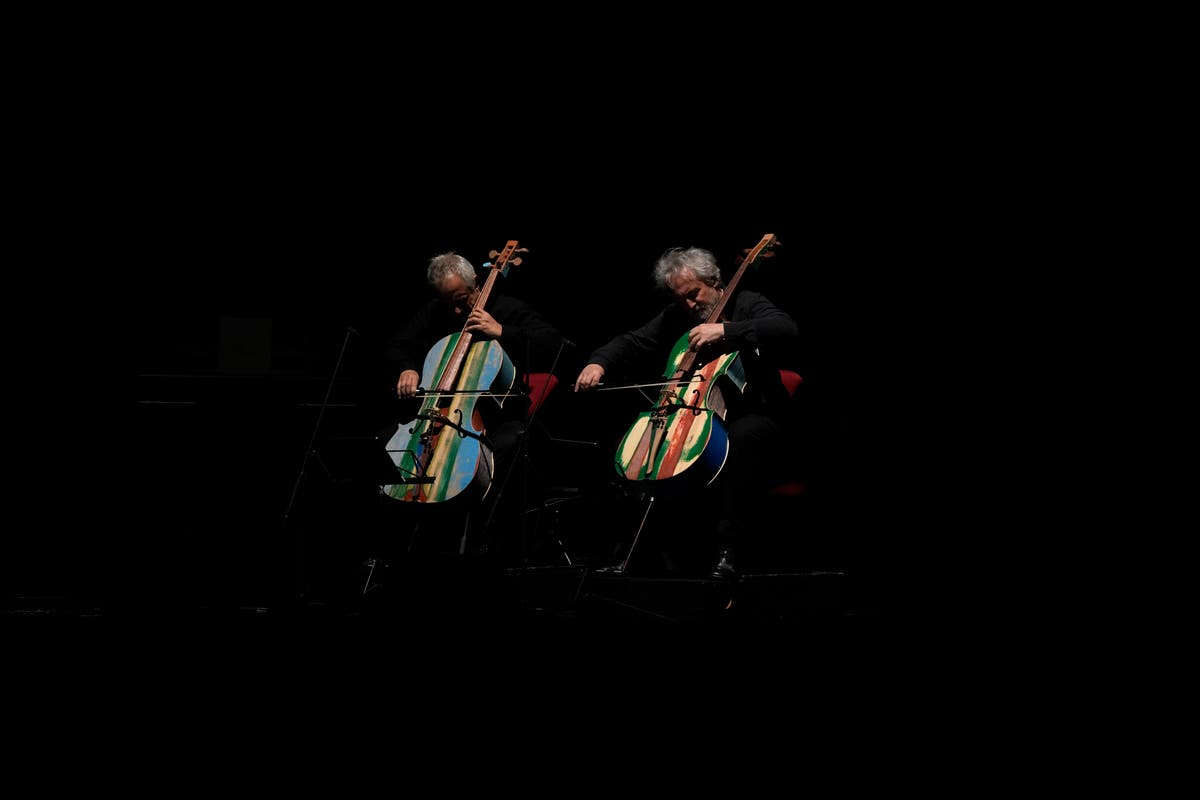

Each instrument takes 400 hours to build, from boat disassembly to finished product. Classical violins made in Cremona’s famous workshops, an hour’s drive from Milan, are made of fir and maple, but sea instruments are made of softer African fir, sun-drenched blues, oranges, and Assembled in shades of orange. Red remains as a memory of the trip. The painted veneer affects the tone of the instrument.

“There is a sweetness that cannot be imagined in these instruments that have traveled across the ocean,” said cellist Mario Brunello, a member of the Orchestra of the Sea. “They don’t have a story to tell. They have hope and a future.”

The House of Spirit and the Arts Foundation, which was the first to introduce luthier-making workshops in four Italian prisons 10 years ago, says the La Scala concert marks the beginning of a movement that will bring sea orchestra performances to southern European countries for the first time. I hope. Northern capitals bear the brunt of immigration and then have the most influence over immigration policy.

“The beauty is that music transcends all divisions and all ideologies and touches people’s hearts and souls, and I hope that music makes people think,” he said, adding, “Politicians need to think about this drama. “There is,” he said.