Written by Tony Le Calvez (Blunt Scholar, 2022)

With the opening sound of castanets clinking, Miles Davis and Gil Evans transport me to the streets of Cordoba. I smell the dust (I inhale it), I see the warm light of the light bulbs hanging between the roofs (the night air is clearly visible), I see the heat accumulated during the day radiating from the walls. I feel (the adobe is whiter than my skin), I smell the sweat (when I work and when I’m resting), I smell the sweat (when I’m working and when I’m resting), and the tip of my tongue (when I’m brave) taste of bull’s blood.

When the castanets leave, the street disappears and I’m alone in the corrida, surrounded by glittering horns, menacing string instruments, Miles’ trumpet, picadors, bandellieros, and torero bullfighters. Sand clogs my nose and clings to my damp skin. I tried to look into the bullfighter’s eyes, but his eyes were closed.

The first side of the Davis & Evans record Sketches of Spain opens with Joaquín Rodrigo’s evocative 16-minute overture, Concerto Aranjuez, which Miles claims he nailed. The piece fluctuates between majestic blasts of horns, paradisiacal sounds of castanets, and rolling bellows of bass brass. Between these shifting emotional tones, the string bass flicks a small foothold as the accompaniment instruments navigate the song’s less defined elements, whether in the high or low registers. . Miles’ horn lines can’t even be called melodies, they’re like gusts of wind, hard to grasp, pushing me in whatever direction they choose.

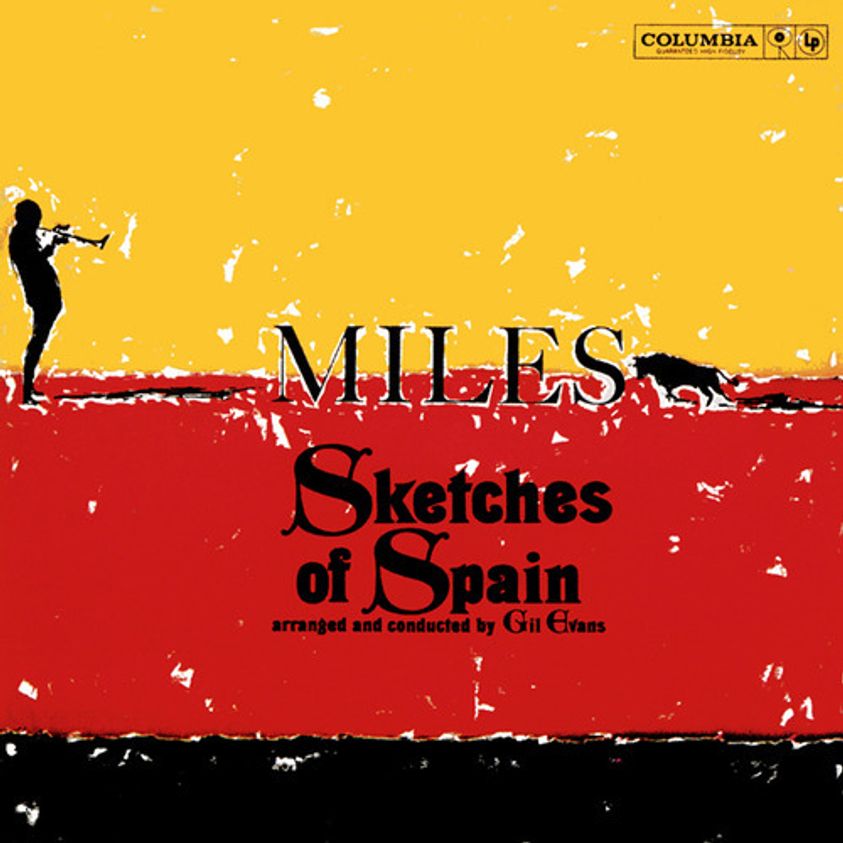

It was this song that inspired Miles to record a complete set of jazz, flamenco, and Andalusian folk music. He and Evans, the record’s arranger and conductor, collaborated to adapt the trumpet to the sounds and moods of songs normally created for guitar. After extensive research into contemporary and traditional Spanish genres, they decided on five of his works to serve as canvases for sketching this Spanish aural figure.

As the track progresses, I am no longer in the corrida, but in the stands. I watch from a distance, and everything is clear: the bull’s bloodshot eyes, the flash of yellow on its hooves, the trumpeting glow of its sword. When the singing stopped, the silence made my throat stiff. I had never seen this bull before, but something about him seemed familiar. Not his broad shoulders or tall stature, but something else, something I could feel. I try to remember, but the memory is so far away that when the song ends, the memory fades with me.

In the second song, “Will O The Wisp,” it’s not Miles’ voice that carries the melody, but his shadow. Dancing to an indistinguishable time signature, his shadow leaps up and down the boulevards and boulevards of Evans’ arrangement, attaching himself to the listener and giving him a sense of his body: legs, legs, arms, movable limbs, a sense of objectivity. I’ll blow it in. , and the forms that can inhabit this fabricated vision of Spain. Flashes of color emerge from the accompanying ensemble. Like the swaying swell of a clarinet, the roar of bass brass, the smile of a stranger who nods hello as you pass, or the unexpected voice of a friend randomly calling your name from across a dimly lit bar. I got lost. The landscape appears under a bell-shaped shadow. It’s fabricated, but exciting and relatable.

Despite Miles and Evans’ wistful invitations to nostalgia, I am haunted by a vision: the solemn cry of a speared bull. The mirage disappeared as I sifted through the blood-red sand of reality. I’m on my great-grandfather’s land. Once upon a time, this land was divided between fascists and freedom fighters, Francoists and republicans, dragons and bulls. The Republican Party, including my great-grandfather, was unable to stop the overwhelming Quadrilla of that forked-tongued Torero Francisco Franco. On the hot sands of the corrida, the bull fell alone, confronted on his back by a ferocious banderilla, stabbed through the heart. The vision fades like a bone in the sand, and Side One ends.

I heard Miles’ horn calling to me like a kestrel’s call, and I stepped back into his shadow. Side two began with “The Pan Piper”, with Miles changing the horn from guitar to flute. In fact, despite being accompanied by three flutes, his horn outweighs them in the song. Hypnotize them and make them dance for him, like enchanted mice (or children). This short, tactile piece feels light to the touch, like the details in a painting that captures everyday life: crickets on the grass, reflections in the water, a mother holding her child’s hand as they walk toward the park. Masu. This melody originates from the song played by Galician pig castrators as they enter the city to drum up business and make their presence known. You can hear him play, but you can’t see him work.

When I close my eyes, the fourth song, “Saeta,” transports me back to the street, but this time Miles is playing along the balcony and in the rain gutter. I’m not standing alone, I’m following the procession. Someone died, but I don’t know who. All I know is that I should be silent and pray. Like a nosy neighbor peeking out of a doorway, Melody accompanies Miles as he wanders the rooftops, but not all streets are the same. It’s Granada, Barcelona, Pamplona, yes, but it’s not Spain now, it’s Spain. The same paths my great-grandfather walked, ran, and was chased. What distinguished him was not his broad shoulders or height, but the sweat dripping down his face. It smells nostalgic.

I’m currently running on line 5. The roar of the harp adds an atmosphere of Cervantes’ magic to the space between the horn fanfares, and when the vibrations of this energy hit my ears, it makes my heart race. Searing cymbals take control back, reminding us that this is still a jazz piece. It’s not just a hybrid of modern flamenco or Andalusian folk revivalism, but a truly unique combination of styles and sounds brought to you by Miles’ passion and Evans’ musical talent. Their disciplined research and ingenious innovations have created a sketch of life as it once lived, but it is just that: a sketch. That’s not real life. It’s a vision, a dream, a lament, a hope, and I run towards it, but I never find it. It’s muleta.

Like many others, my great-grandfather fled, leaving everything behind. Not to the fields and retreats of Elysia, but to France, a land soon to be occupied by the fascists themselves. He went into exile and never returned home. Home, where his sweat has salted the ground, where the sun has dried the sand to a pulp, where the ground is thirsty for a drink. I can’t tell if it’s wine or blood. It’s just an album, it’s just a sketch, it’s not real, it’s a muleta, but the familiarity is enough to dive right in. Eighty years later, when I close my eyes, Davis and Evans take me there. I know because the smell of that sweat is mine.