The 2020 Nobel Prize was awarded as a major biomedical breakthrough for CRISPR technology for genome editing, which has the potential to save the lives of many people suffering from genetic diseases.

There is now international consensus that the use (or abuse) of genome editing for human enhancement is unethical. It is unethical to use genetic engineering to obtain desirable traits in intellectual or athletic ability, or physical characteristics such as skin color or height.

However, genome editing of somatic (non-reproductive) cells to treat genetic diseases is widely considered acceptable. And there are currently several clinical trials underway in this area.

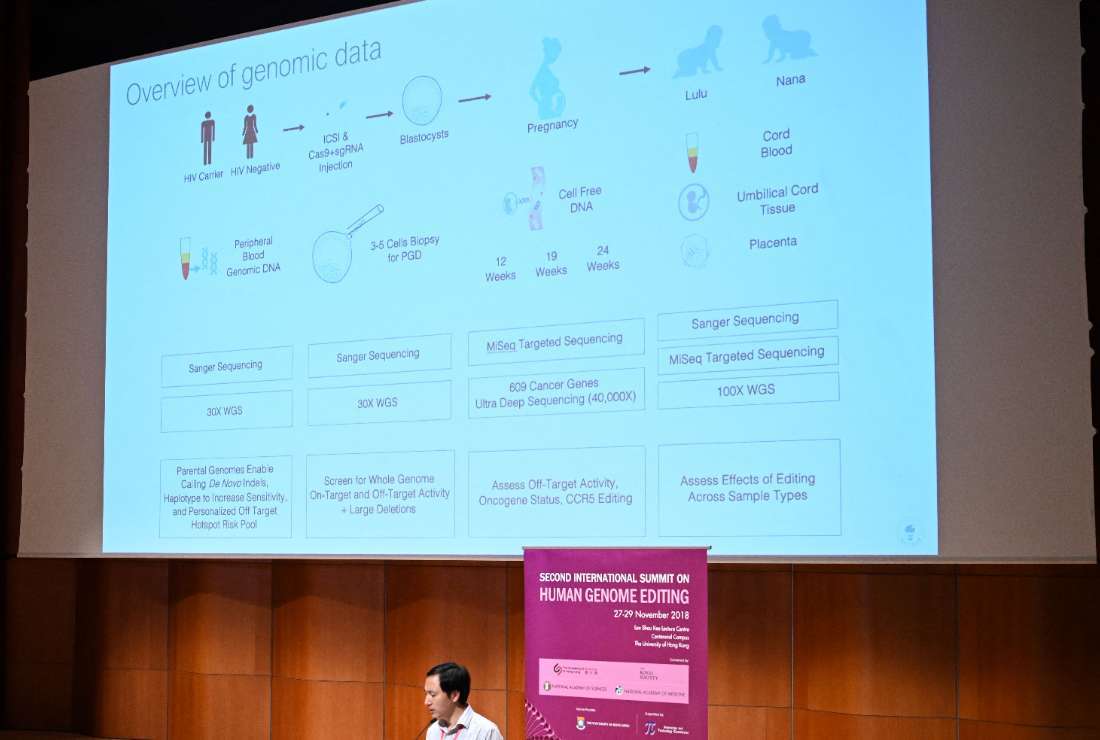

Still unresolved are the ethical issues in genome editing of human embryos and reproductive cells (germline) to prevent inherited diseases. This is best exemplified by the infamous case of Chinese scientist He Jiankui, who was sentenced to prison for editing the genome of human embryos to confer resistance to HIV.

Such controversies are certainly of interest to the ultra-wealthy and tech-savvy city-state of Singapore, which has invested heavily in biomedical research in recent years and has developed a comprehensive system of biomedical regulation and ethical review. It will become a thing.

There are several ethical and moral issues that must be resolved when Singapore decides whether to allow genome editing of human embryos in IVF treatments.

I won’t try to save your life

Genome editing of human IVF embryos is not life-saving in itself, but rather aims to save the lives and health of unborn future descendants, and is therefore used to treat patients suffering from life-threatening genetic diseases. It is much less necessary and urgent. .

The primary goal here is to allow patients with known genetic defects to produce healthy, genetically related offspring on their own, rather than adopting or relying on egg donation. It should be.

This is consistent with Singapore case law, which emphasizes people’s desire to have a child with their genes as a basic human drive. This is also consistent with Singapore’s socio-cultural values, which are primarily Confucian-centered, which emphasize continuity of lineage in traditional family formation.

Another major issue is the availability of safer and less complex options, particularly preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) of human embryos, to prevent the transmission of known genetic defects to future offspring. be. The question arises: If PGT is a readily available option, why use genome editing?

PGT is a mature technology platform that has proven effectiveness in screening and eliminating a variety of known genetic defects in IVF embryos. Compared to genome editing of human embryos, PGT is much safer as there are no permanent genetic modifications that can be passed on to future generations. This is essentially a technique for screening in vitro fertilized embryos for the inheritance of certain known genetic defects.

Nevertheless, in some cases, genome editing may be preferable to PGT. For example, there are typically very few healthy IVF embryos produced by older women, providing a small sample pool. This may not give us much choice in selecting for the non-inheritance of known genetic defects, so it may be worth the risk with genome editing.

Additionally, older women tend to produce weaker, lower-quality embryos and may be more susceptible to damage from cell extraction (biopsy) for genetic testing. Other cases may include rare instances where both parents have the same genetic disease, especially one with a dominant rather than a recessive genetic mutation, such as neurofibromatosis.

Yet another option is to perform gene therapy on the fetus while it is still in the womb. Prenatal diagnosis of genetic diseases uses advanced surgical techniques to extract cells from the fetus, edit the genome, and then reimplant them into the fetus. This is more easily accomplished because there are millions of cells available in the fetus, as opposed to the few cells in the fetus.

Genome editing redundancy

Due to permutations in the recombination of various genes during the fertilization process, some embryos may inherit known genetic defects of their parents, while others may be healthy. When genome editing is performed indiscriminately on entire batches of IVF embryos before identifying embryos with known genetic defects through genetic testing (PGT), healthy embryos are subject to unnecessary redundant genome editing. You may be exposed to this and may have adverse effects.

There is a contradiction here. When initial genetic testing is required to screen for genetic abnormalities in IVF embryos prior to genome editing. So what is genome editing useful for? Some healthy embryos are already identified during the screening process, making genome editing unnecessary. In rare cases, if all the embryos turn out to be genetically abnormal, the patient can simply try IVF again.

Streamline cost-effectiveness

The occurrence of genetic diseases is relatively rare, and even rarer are the instances where genome editing may have an advantage over PGT in preventing the transmission of genetic diseases.

The extremely small size of the market will raise questions about the commercial viability of editing the genome of human embryos for IVF treatment and its ability to boost Singapore’s low birth rate.

Safety issues in genome editing

Genome editing using CRISPR technology is neither completely error-free nor without potential risks. These include unintentional on-target and off-target gene editing errors, as well as poor editing errors that result in mosaicism in which only some, but not all, cells within an embryo have correctly edited genes. Masu.

Therefore, the number of embryos typically produced by each couple during IVF treatment is relatively small and the sample size is very small, imposing severe limitations on screening for such gene editing errors. . In contrast, millions of non-reproductive (somatic) cells are readily available for genome editing and subsequent screening for gene editing errors.

Furthermore, current knowledge about the complex interactions of genes involved in genetic diseases remains very limited, and there is always a risk that harmful side effects of genome editing may manifest well into adulthood. To do.

Recently, a new study reported that CRISPR gene editing on human embryos could have dangerous consequences. This is because the cells of early human embryos, unlike other non-reproductive (somatic) cells in the human body, are often unable to repair DNA damage caused by genome editing processes.

Considering the various controversial issues and shortcomings associated with genome editing of human embryos to prevent genetic diseases, and given the very small market size and limited commercial feasibility, Singapore Investing and developing genome editing of human embryos in IVF treatment may not be worth it. .

It has been speculated that the only commercially viable and lucrative market for genome editing of human embryos may lie in applications for human enhancement rather than disease prevention. However, this is unlikely to be allowed in Singapore given the current government policy that biomedical regulations in Singapore must comply with international agreements and standards.

* Based in China, Dr. Alexis Heng Bun Chin previously worked in the field of human clinical assisted reproductive technology research in Singapore, and in addition to publishing more than 250 scientific papers, she is an expert in new reproductive technologies. He has authored 50 international journal publications on relevant ethical and legal issues. Journal article. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of UCA News.