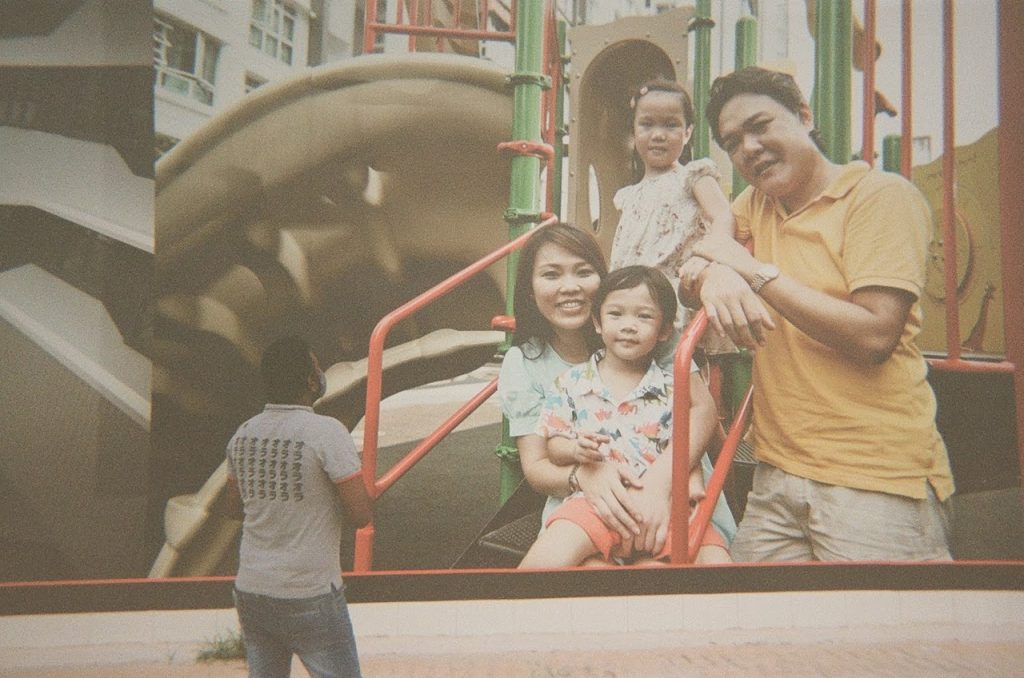

Top image: Benjamin Tan / RICE file photo

This story is part of RICE Media’s Storytellers initiative, a mentorship programme for budding content creators to learn about the art of creative non-fiction. This piece is a product of a partnership between RICE Media and Singapore Management University (SMU) for its Professional Writing module.

Killing a version of myself was the only way I could ever be loved. It was the only way I could ever feel safe as a queer Singaporean.

For years, I’ve had to kill who I truly am, a closeted gay woman, and hide my dead body under my replacement: a heterosexual, norm-conforming female. There was no other solution.

To the first person I tried coming out to when I was 16: thank you for telling me to shoot myself if I can’t be straight. I heeded your advice. The buried identity can concur.

Coming Out and Letting In

Coming out of the closet to your loved ones is considered a rite of passage for any queer person in the LGBTQ+ community. Unfortunately, coming out of the closet in Singapore can also be the scariest thing on Earth, especially when your safety might be compromised.

For ProutApp founder Ching, a lesbian mother of one, safety is not just about feeling safe enough to come out.

“Coming out is an ongoing process (right)… it’s not just about coming out; it’s also about letting people in,” she explains.

“And you let people in because you start to be comfortable with them, you feel safe with them, and that’s why you let them in. It’s actually more of an intimate and personal process.”

Many times, this lack of safety creeps up on closeted individuals, brewing a fear of ostracism that forces them to stay in their closet. This is especially prevalent in Singapore, where society, albeit increasingly progressive, still remains largely conservative when it comes to the queer community.

Because of this, closeted individuals would rather ‘let in’ their loved ones into their queer lives instead of ‘come out’. This feeling of safety and comfort is considered to be a “baseline requirement” for people in the LGBTQ+ community when coming out.

“I felt that we were close enough to have that understanding that, you know, nothing bad was going to happen. Like I didn’t think they would turn me away or anything like that. So I guess in that sense I feel safe enough just to say it out,” said Cameron, a trans man who first came out to his close friends back in primary school by asking them to address him using his chosen name.

Shortlisting the right people to come out to is potentially a life-changing decision that LGBTQ+ individuals have to make. These people don’t necessarily have to be an ally or supporters of the LGBTQ+ community, and coming out to them is a benchmark for whether or not they’re people who genuinely care.

These are the people who love you unconditionally.

The Condition of Unconditional Love

“Love should be unconditional.”

That’s what Siti*, a semi-closeted (open about her sexuality with her peers but not her family) gay woman, had to say about the definition of love. Ironically, for a significant part of her life, the love she had for herself was anything but unconditional.

She had conditions for herself—conditions that made her feel lifeless and unmotivated. Conditions that forced her to become her harshest critic. Holding back tears, Siti feels that her conditional self-love could have stemmed from the trauma she endured as a victim of child sexual abuse.

“It made me doubt whether my sexual identity was nature or nurture. I hated knowing that my identity could have possibly been shaped by the actions of my perpetrator.”

Siti’s perpetrator passed on several years ago, leaving her with excruciating memories she wished she could forget.

People in the LGBTQ+ community find it challenging to love unconditionally due to a multitude of conditions that their sexuality in itself fails to fulfil. This love is not just about loving others but also about loving yourself. Owning your identity and being able to love yourself for who you are, regardless of whatever has happened in your life, is the first and most fundamental step to loving unconditionally.

This wasn’t the case for Siti, who, just like many others in the LGBTQ+ community, share the same sentiments that their sexuality is as such because of the experiences that groomed them.

Unbeknownst to many, this nature versus nurture debate is a longstanding internal struggle for many in the LGBTQ+ community. Although various studies and research papers will show that sexuality is indeed nature and not nurture, this internal struggle still remains pervasive in many lives.

Not only does this indicate a lack of acceptance towards their own identity, but it is also considered an act of conditional love; they will only love and accept themselves if they conform to a certain persona. Most of the time, sadly, this ‘persona’ conforms to societal norms: straight and cisgender.

An important prerequisite of unconditional love is to embrace the person receiving this love for who they are. Unconditional love is meant to be a type of love that is not bound by any conditions under any circumstances. Funnily enough, one condition defines unconditional love: that it should be limitless regardless of any circumstances in life, including one’s identity.

Praying the Gay Away

Unconditional love, or rather, the lack of it, ties in very closely with the emotional, psychological and mental well-being of LGBTQ+ individuals.

Love that has conditions—specifically, conditions pertaining to one’s identity—forces LGBTQ+ individuals to stay in the closet due to the impending fear of ostracism as well as the fear that their loved ones will cease to love them for who they are. These rules that define the quality and magnitude of love given and received are known as conditional love.

In an Asian family, it is the unfortunate commonality that the love you receive is, more often than not, conditional. They want the best for their loved ones, and having perfectionistic expectations of their loved ones is their way of showing that they care for you.

This is coupled with the fact that most Asian families are conservative—not fully accepting of the LGBTQ+ community and extremely self-conscious of their image. Because of this, it is not uncommon for a person to be unable to continue loving someone else when both of them have differing beliefs and values.

Growing up, I had an inkling that my family’s love might be conditional, especially when it came to being queer. At the dinner table, they would warn me, “You better be careful… Don’t become lesbian, or I will shoot you.”

I valued their opinions, whatever they may be. But to uncover the shattering reality that my loved ones might not be accepting of my sexuality created a fear that consumed me for years on end.

The truth is, nobody wants their loved ones to stop loving them. We all want our loved ones to be proud of us, to get their approval, to be loved by them. The last thing we want is for our identity, something that is so intimate and personal about ourselves, something that is literally ourselves, ruining our relationship with our family.

It’s been almost a decade, and while I’ve worked up the courage to come out to some of my closest friends, it’s still an ongoing struggle to do the same when it comes to my family. This is a responsibility that many of us in the LGBTQ+ community feel weighed down by.

On top of that, Singapore is a multi-religious society, with some religions being more sensitive than others when it comes to LGBTQ+ issues. This affects LGBTQ+ individuals’ decisions on whether they feel safe enough to come out to their family and prolongs the coming out process.

In his decision-making process of when and how to come out to his family, Cameron felt that religion was one of the more important considerations.

“I was raised in a Catholic family and was worried it wouldn’t go well”.

Cameron made multiple attempts throughout his teenage years to come out to his family. However, these attempts would be brushed aside, claiming that he was “too young to know” and that there were “no signs” or “indications” to show that he was not cis-gendered.

For many years, Cameron felt unseen, unheard, invalidated. He felt like only as a ‘she’ could he belong. During this period, he suffered from mental health issues and dysphoria just so that his parents could still have the daughter they desired.

Cameron wasn’t the only one. Coming from a Muslim family, Siti grew up with the mindset that she was born into her religion and had to be loyal to her faith by “praying the gay away”.

“You will grow up believing whatever is told to you”, she says, adding that she believed the teachings of her parents and believed them when they told her that being gay is a sin.

For the most part, our personalities, beliefs and values are a reflection of our parents, which ultimately results in mental dilemmas when we realise that we might not conform to said beliefs. In more severe cases, such as Cameron’s and Siti’s, it could result in depression and anxiety.

All of these mental health issues are exacerbated when our loved ones’ love is conditional. Love shouldn’t be conditional—let alone break someone to the point of nothingness to fulfil that one condition that, at the end of the day, means absolutely nothing compared to their happiness. That is the cold, hard truth.

Establishing the Definitive You

Your achievements don’t define who you are; your identity does. Your sexuality defines who you are, for your sexuality is your identity.

Yet, conditional love is something that people in the LGBTQ+ community face sooner or later from their loved ones because of their non-conforming identity. The sickening irony is that your loved one’s conditional love for you is limited to who they want you to be and not who you actually are.

Conditional love presents many consequences, whether they be emotional, physical, psychological or mental. It is traumatising and heartbreaking to know that not only do I, but others too, have to go through so much anxiety and emotional turmoil, battling our inner demons just to convince ourselves to take the risk of losing our loved ones to conditional love.

The amount of courage and effort it takes just so that we can ‘confess’ that so-and-so is our sexuality and is what we identify with when, in the first place, identity should never be a confession.

Anyone and everyone in the LGBTQ+ community should feel comfortable and safe enough to come out to their loved ones anytime, anywhere. The whole process of coming out and letting in should not be done with the intention of escaping the risk of facing conditional love from loved ones, but rather; with the intention of being proud of who you are as a person. No matter whether you are gay, straight, bi, lesbian or living the transgender life, at the end of the day, you are whoever you choose to be.

You live for yourself and only yourself. Nobody gets to make that decision except for you.

Today, Ching continues to give back to the LGBTQ+ community by being part of the organising committee for Pink Dot and also lives her life to the fullest with her wife and daughter, where unconditional love blazes strongly within the family of three.

As for Cameron, his family has started to realise the impact of conditional love on him in recent years, and they’re currently on a steady route in supporting Cameron’s transitioning process by trying to understand him and loving him as a son.

Siti went through so much and came out even stronger than before. She has my utmost admiration and respect as someone who’s now standing tall and proud of who she is, no longer letting conditions dictate her love for herself.

Last but not least, there’s me. 2023 was the year I decided everything would change. I’ve undug my once-buried identity and found a partner now, a beautiful being who has shot me with bullets of unconditional love, told me to live daringly, and shown me that it’s okay to be me and still be loved. Unconditionally loved.

Unconditional love is something that anyone is capable of, whether it be to others or themselves. All it takes is to accept someone wholeheartedly. Everyone deserves unconditional love regardless of race, language, religion, or identity.

*Name has been changed