The BRI has evolved from a surplus dump to a financier of big infrastructure. It has scaled back its economic ambitions but remains a political tool for Xi Jinping.

In a nutshell

- The initiative’s purpose has evolved and now embodies Mr. Xi’s global aims

- Beijing overlooks debt and tolerates corruption in recipient countries

- Projects are smaller, but BRI remains influential and is likely here to stay

While Chinese President Xi Jinping was celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2023, the media from China and the West seemed to be caught in a trap of their own making, with one side praising it and the other criticizing it mercilessly. However, the Chinese government has quietly begun to change its approach. Whether anyone likes it or not, the BRI has had an extraordinary impact on the world by improving infrastructure in poorer areas of Asia, Africa and Latin America while boosting Beijing’s diplomatic reach. It may be time for a global rethink of the BRI.

Original intent and Xi’s windfall

The BRI was started to solve China’s product glut (steel, cement and other such basic materials) and to make more efficient use of China’s foreign exchange reserves through lending. This neo-mercantilism aimed at dumping more products into Europe and other regions. Up to now, the initial goal was only partially realized, including the building of additional infrastructure, such as freight railroads from various parts of China to Europe.

Over time, BRI aims shifted and expanded globally: as of August 2023, about 150 countries had signed up to the initiative. The BRI ended up serving as a valuable platform for developing President Xi’s ambitions as a world leader. The BRI also presented an opportunity to export Chinese goods to countries that are not affluent and to extract natural resources from those developing nations. The data suggests that Asia, Africa and Latin America have become important destinations for commodity exports, accounting for about 21 percent of China’s total exports in 2022, according to official Chinese government figures.

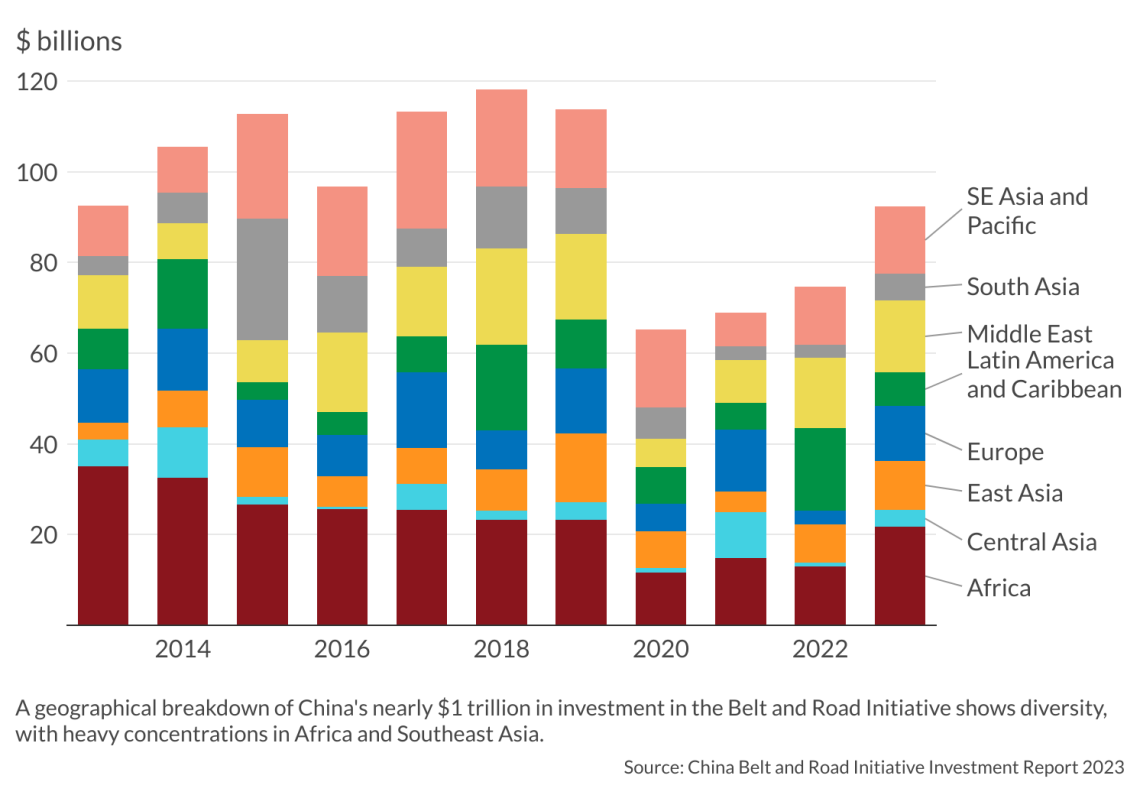

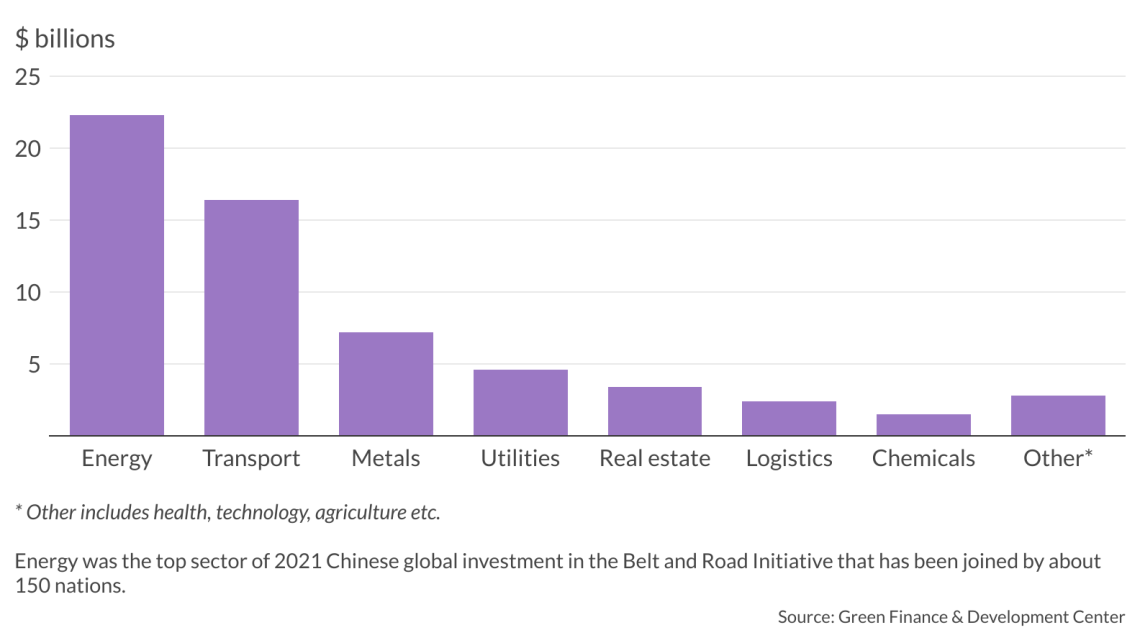

At the same time, China has invested in many unprofitable infrastructure projects in several countries. According to Chinese official figures released in 2024, the debt owed to the Export-Import Bank of China by countries participating in the BRI has reached more than $300 billion out of China’s total engagement of roughly $1 trillion since the start of BRI. According to a recent study from Griffith University in Australia and Fudan University in Shanghai, China’s investment into BRI countries last year was the highest since 2018, and almost 80 percent higher than in 2022, with Chinese companies directing almost $50 billion into overseas projects. The total engagement includes about $600 billion in construction contracts and about $420 billion in non-financial investments, according to the Green Finance and Development Center in Shanghai. At first, China saw generosity in granting credits as an important feature of the BRI projects. But now, the inability of debtor countries to repay their loans is increasingly troublesome to Beijing, which has announced a policy shift to “small and elegant” projects; these less frequently involve infrastructure construction.

Economic considerations have often given way to more political tradeoffs. Beijing pressured some state-owned enterprises to participate in Belt and Road projects in certain economically less attractive countries such as Belarus. There are certainly many impressive projects. However, they were often accompanied by dark sides. Many beneficiary countries took advantage of the BRI projects to breed new forms of corruption. Finally, China’s imperial style made it impossible to guarantee the quality of the projects. One such case is Nepal’s poorly built $216 million international airport. Chinese contractors are accused of ignoring international best practices in the bidding process and inspections.

Due to insufficient due diligence, China has not been able to receive its expected return. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a prime example. It was the flagship of President Xi’s handpicked projects, with more than $100 billion in related investments. Several projects were thrown into disarray during the 2018-2022 period when the government of former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan raised allegations of corruption. The scandal was so gross that on the 10th anniversary of the BRI, it disappeared from the public narrative.

Considerable undertakings have not brought much tangible benefit to China’s economy. The BRI began to be overshadowed by geopolitics when the U.S.-China trade war began in 2017. And now, after a decade, it has become a tool for President Xi to build a “road to a new global order.”

President Xi’s confidence suggests that he is satisfied with the benefits that existing Belt and Road projects have brought China and the Global South countries, as well as Russia, Hungary and Serbia. His ideas — the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security Initiative or the Global Civilization Initiative – are pursued by the Chinese Communist Party and other officials as part of his vision of a new order.

Beijing departs from Western aid practices

Regardless of the amount of corruption and indebtedness in China’s 1,000-odd projects, the BRI and its implementation are, after all, a Chinese innovation. Beijing is indeed breaking away from the framework of existing Western aid practices for developing countries and trying to introduce a different approach to meet the modernization needs of countries that are short of capital, infrastructure, technology and human resources.

The Chinese government’s concerted and rapid coordination and deployment of resources is often evident in the implementation of projects. When Huawei helped build telecommunications networks in several poorer African countries, the Chinese government quickly helped them pay for Huawei’s projects by facilitating the export of agricultural products or minerals to China.

This kind of all-encompassing coordination would be unthinkable in the West. However, this practice is a logical extension of China’s approach to international engagement, which overlooks corruption, a feature that has made China’s help attractive to several developing countries.

Facts & figures

Adjustments do not mean failure

Beijing isn’t sticking to the practices it started with. Back in 2017, at China’s second BRI Summit, the leadership had already changed its approach as it felt that it was financially out of its depth. Some statistics show that China’s infrastructure activities under the Belt and Road framework have decreased by 40 percent compared to 2018. China’s lending to Africa in 2021 and 2022 was below $2 billion, a 20-year low.

At last year’s third summit, President Xi signaled that China would inject another $100 billion into the BRI. But more importantly, he emphasized that BRI cooperation will move from “giant projects” to “fine brushstrokes,” indicating that 1,000 smaller projects benefiting people’s livelihoods will become the new normal. In other words, due to economic difficulties at home, Beijing will no longer be so generous in lending.

However, big infrastructure projects will still come when the respective countries have high significance from Beijing’s geopolitical perspective – the more geopolitically antagonistic the region, the more willingness to shoulder the cost burdens. For example, President Xi recently offered to help Vietnam upgrade its railroads and other infrastructure with grants – not loans — during his visit to Hanoi. Beijing is ready to invest in Vietnam because it is seen as a solution to China’s efforts to circumvent Western sanctions.

Many Western observers are missing the point when they conclude China’s downsizing of projects is a failure of President Xi’s BRI design. Indeed, from Beijing’s perspective, success and failure are not just an economic account but a long-term, all-encompassing political investment. Such an approach is unlikely in countries that are predominantly market economies and democracies.

Take the example of Laos, a BRI participant with more than $1.4 billion in debt. The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) is below $20 billion, it cannot pay its debts. But Beijing is thinking not about short-term return. China seeks long-term control over the landlocked nation of nearly eight million people. As China invests in Laos, it trains many professional cadres for the country, inviting them to earn degrees at Chinese universities. The thinking here is that if these people work as decision-makers in key Laotian government departments in the future, their repayment to Beijing will certainly be realized.

The Global South lacks capital and technology. China’s presence, along with the BRI project, is possibly a development opportunity for these nations, though long-term risks are uncertain. Regardless of numerous setbacks, China benefits by financing modernization projects with its assets: the Beidou navigation system, Huawei’s telecommunications, renewable energy and artificial intelligence, just to name a few. The West now seems inclined to follow a similar path in infrastructure development while China turns to business investment and expansion on other continents.

Facts & figures

Opportunities of modernization if elites are smart

Both the United States and the European Union are trying to catch up to China in investment in parts of the globe. However, a lot of ideas are still at the design level, such as the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and a plan to assist African countries in building a cross-country railroad.

In any case, the West wants to show that it cares about the Global South, presenting an opportunity for countries in urgent need of modernization. Of course, whether those countries will be able to make good use of such opportunities depends on the integrity and wisdom of recipient governments.

Indonesia may be a case in point. Recognizing China’s eagerness to set an example in Southeast Asia and its own desire to modernize, Indonesia tries hard to avoid becoming an indebted country. The Jakarta elites made a deal with China to accept BRI projects based on the transfer of cutting-edge technology and the training of human resources. At the same time, no government-to-government loans will be taken.

Indonesia is the first country in Southeast Asia to introduce China’s high-speed rail, but the project will not be profitable for 30 years. Indonesia’s leadership is also aware that its telecommunication industry has become dependent on Huawei.

Scenarios

Likely: President Xi’s brand of diplomacy carries on

The decade of the BRI has brought about many changes in the world’s politics and economy, both positive and negative. This change is reflected in the soft export of China’s authoritarian rule and culture to recipient countries. Other nations’ political elites covet Beijing’s modern industrial products and technologies. Many of these elites are not thirsty for democracy but have an urgent need for modernization.

The BRI is not only part of the political competition between the West and China, but from an economic point of view, much of what Beijing is doing is intended to challenge Western standards.

For example, China has not adopted the haircut approach to restructuring the debt of African countries, as is common in the International Monetary Fund and the Paris Club, but has insisted on extending the repayment period or lowering the interest rate by its practices. All of this is not easy to accept from a Western perspective.

Many developing countries will be disappointed that China will not be able to lend generously for infrastructure tasks in the future. However, they will have to adapt quickly to China’s “small and elegant projects.” China will steadily expand its already well-established bases, such as in the mineral-rich countries of Africa and Central Asia. However, Southeast Asia will continue to be the focus for China due to its geographical and cultural proximity.

The BRI has become President Xi’s brand of diplomacy. Of course, how well China’s economy develops will determine whether future projects go smoothly. In the short and medium term, it can remain a bright spot in Chinese diplomacy as long as President Xi is in power.

Unlikely: A weaker economy forces China to abandon BRI

An unlikely scenario is that China’s economic deterioration accelerates, and Mr. Xi makes one diplomatic mistake after another, putting an end to BRI quietly. Even so, Mr. Xi would not publicly admit it as a mistake, just like how the zero-covid policy abruptly ended. Even so, the tie to the mineral-rich countries, or countries that are of great importance in geopolitics, will be continuously maintained, regardless of the future fate of BRI. China has established a formidable manufacturing base, which – barring the outbreak of war like an invasion of Taiwan – means economic collapse is unlikely. This position renders China indispensable for developing countries.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.