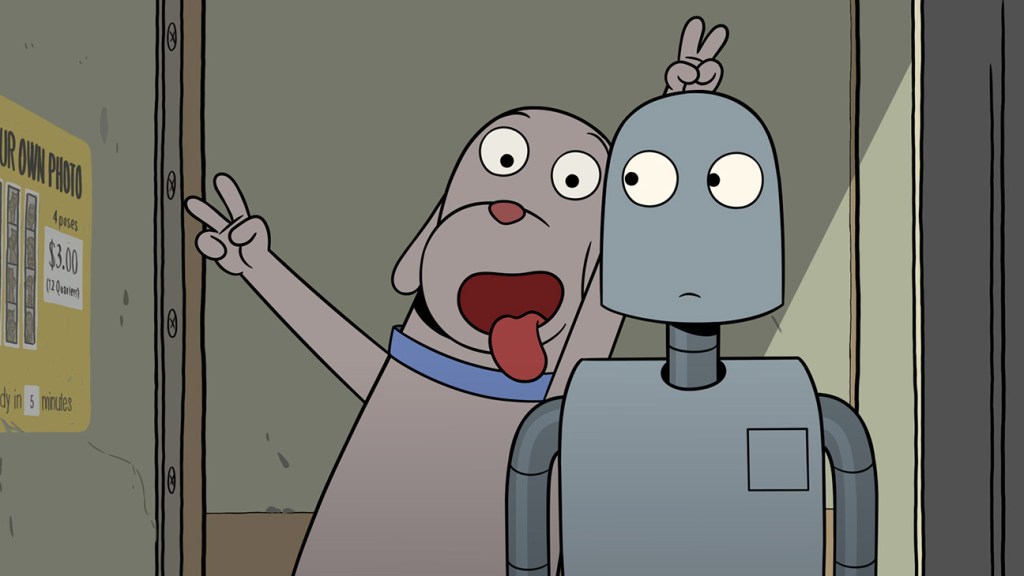

‘Robot Dreams’

Cannes Film Festival

Orson Welles famously started but never finished an adaptation in Spain of Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes’ beloved 17th-century novel. Terry Gilliam’s first attempt to shoot his take on Quixote fell apart so spectacularly in 2000 that it resulted in a widely viewed “unmaking-of” documentary titled, grimly, Lost in La Mancha.

But they weren’t just tilting at windmills. Gilliam completed The Man Who Killed Don Quixote nearly two decades later, making it one of literally dozens of screen adaptations from around the world based on the widely published novel. In April, Oscar-winning director Alejandro Amenábar (The Sea Inside)will start shooting on The Captive, an origin tale about a young, storytelling Cervantes in an Algiers prison in 1575.

Spanish literature — and its literary figures — have been inspiring filmmakers since the dawn of cinema. According to a now-defunct Cervantes Virtual Library database, considered incomplete by some accounts, in Spain almost 1,200 literary adaptations were produced or co-produced between 1905 and 2013.

Today, “the interest in books for possible film adaptations has been increasing year after year,” according to Anna Soler-Pont, founder and director of Barcelona-based Pontas Literary and Film Agency, which has been in the business for more than three decades and represents authors on five continents.

Recent successes are fueling competition for source material, particularly in certain genres, while directors and producers say they’re being approached by publishers earlier than ever before. “In the last 10 years, there have been more and more literary adaptations,” affirms director Isabel Coixet, the European Film Academy’s 2023 European Achievement in World Cinema Award winner.

“In the last month, I think I’ve been offered five adaptations from different countries,” Coixet says, “and I thought I was never going to do another adaptation!” Coixet’s most recent drama, Un Amor, was based on the best-selling novel by Sara Mesa, and in 2017 she won a best international literary adaptation prize at the Frankfurt Book Fair (as well as top Goya Awards) for her adaptation of author Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Bookshop.

Researchers in the field see new trends, such as an interest in younger and more diverse authors and formats, including comics, as well as writer-directors adapting their own works, for example from the theater.

Directors find inspiration in all kinds of stories. Pablo Berger, whose graphic novel-inspired animated feature Robot Dreams recently won best adapted script and animated feature Goyas and is now nominated for an Oscar, describes discovering American author Sara Varon’s wordless book when his daughter was a toddler learning to read.

Years later, he recalls, “I was having a coffee in my office and procrastinating, and I took out the book and read it again, and again I was fascinated. I thought it was funny, unique, surreal. When I got to the end, I was completely, deeply moved.” In that moment, he says, he envisioned the film he would make.

For producers, adaptations can be “a safer bet,” as Coixet puts it, “because there’s something to start with. It’s not just an idea or a plot you’re presenting. A book has a structure, a plot, characters, themes, and for a producer or a platform or whoever is going to finance a film, there is something to start with.”

A book can also come with a built-in audience. “Having an IP behind any project always makes it attractive when it comes to production,” ventures screenwriter Arturo Ruiz Serrano, who collaborated on the script for HBO Max’s upcoming book-based series When Nobody Sees Us. “If a story has worked among readers, why wouldn’t it do so on screens?”

Soler-Pont agrees: “There’s no formula, but I think that is a key element for producers and for platforms before deciding to acquire an IP,” she says. “The platforms have enforced this trend because books with a certain readership already attached will bring consumers to their products.”

Robot Dreams producer Sandra Tapia Díaz of Barcelona-based Arcadia Motion Pictures says 40 to 50 percent of their productions are adaptations of published works, plays or real stories. “A producer can like a story and two things can happen: either the story isn’t a big commercial success, which doesn’t mean it’s better or worse, or it can be a sales success, in which case you’re adapting a novel that has a community of readers, and that obviously becomes an important marketing element.”

For example, when word got out that a first-ever adaptation in Spanish of a Wattpad tale, writer Ariana Godoy’s Through My Window, was in the works, “social networks lit up and the phenomenon began to grow exponentially,” says Nostromo’s Núria Valls, producer on what is now a franchise on Netflix. The first installment sat on the streamer’s global non-English top 10 list for a whopping 16 weeks. The third installment, Through My Window: Looking at You, premieres on the platform Feb. 23.

Producers don’t want to miss out, and manuscripts are increasingly selling before publication. Spanish novelist Dolores Redondo’s noir Baztán Trilogy was optioned based on the first book — before publication, and before the next two installments were even written, according to Soler-Pont. All three adaptations — The Invisible Guardian, The Legacy of the Bones and Offering to the Storm — are currently streaming on Netflix.

Now, Tom Winchester of U.K. outfit Pure Fiction is developing Redondo’s 2019 novel The North Face of the Heart with writer Lydia Adetunji (His Dark Materials). He says main character Amaia is “a strong, intelligent and emotionally intuitive woman who already resonates with so many readers worldwide, but this premium adaptation will build on that success and bring Dolores’ epic storytelling to a global audience in an entirely new way.”

Going a step further, Soler-Pont says she optioned the rights to Syrian refugee Sama Helalli’s Spanish-language, female-led crime thriller Operation Kerman to “a big platform” before the work even has a publisher attached (the audio book is available on Audible). “Maybe when this is out there, or when shooting starts, maybe then we’ll have a publishing house interested.”

Coixet and producer Raffaella Leone currently hold the rights to The Lost Daughter author Elena Ferrante’s The Days of Abandonment, a project with Penélope Cruz long attached. An English-language Cruz-Coixet-Leone-Ferrante combo would certainly have international appeal. That’s an obvious plus for producers looking for content — especially at the streaming platforms, which account for more than a third of global content investment in Spain, higher than in any other European territory, according to the 2022-23 European Audiovisual Observatory yearbook.

The streamers have shown particular interest in genre content from Spain, especially true crime, thrillers and young adult romances. HBO Max’s eight-episode When Nobody Sees Us, based on Sergio Sarria’s novel, is a thriller set against Seville’s atmospheric Holy Week processions. Enrique Urbizu is directing from the script by Daniel Corpas, Ruiz Serrano and Isa Sánchez.

Netflix backed JA Bayona’s top Goya-winner (12 awards, including best film and director) and Oscar nominee Society of the Snow, based on Pablo Vierci’s book about real events. The platform is now in production on the second season of popular crime series The Snow Girl, based on the Javier Castillo novel, and Oriol Paulo’s new project, based on Mikel Santiago’s best-seller The Last Night at Tremore Beach, building on the success of Paulo’s previous book-based thrillers, God’s Crooked Lines and The Innocent.

In addition to the Through My Window franchise, the platform has also seen huge success with several series based on romance novels by popular author Elísabet Benavent, including 2023’s A Perfect Story and Sounds Like Love, both of which sat on the global top 10 for multiple weeks.

Amazon has its own ongoing mix of young romances (My Fault, based on a trilogy of books by Mercedes Ron) and thrillers, including the feature Apocalypse Z, based on a book by Manel Loureiro, and two series adapted from best-selling books by Juan Gómez-Jurado: The seven-episode Red Queen, premiering globally Feb. 29, and eight-part revenge thriller Scar, currently shooting in Bilbao.

Martin Scorsese, who recently gave a talk at Spain’s Film Academy, is taking an executive producer credit on Rodrigo Cortés’ Escape, in production at Nostromo and based on a book by Enrique Rubio. Valls says a final edit was recently completed, with Scorsese’s approval.

A film or series adaptation can also give back to its source material. Since the release of Un Amor in Spain, Coixet says sales on Mesa’s book, originally published in 2020 by Anagrama, have taken off again.

Tapia Díaz says they helped get the Robot Dreams graphic novel published in Spain (through Astronave, in May 2022). It ran with a label mentioning the upcoming film, fostering “a community of readers who were awaiting the film, and in turn, a film that returned a cinematographic community to the graphic novel. It’s been a marketing win-win.”

Still, not every author wants to see their work adapted to the screen. Soler-Pont cites best-selling Spanish author Carlos Ruiz Zafón, who died in 2020: “He never sold the rights because he didn’t want to be a ‘traitor’ to his readers,” she says.

“We all know bad adaptations,” notes Ruiz Serrano. “And there are also authors who are more complicated to adapt — Faulkner or Virginia Woolf, for example. But we continue adapting literature to cinema. And that will go on.”

Readers can also be critical of adaptations. “When you adapt a novel, it is very difficult to be 100 percent faithful to the text,” says Ruiz Serrano. “They are different languages. In screenplays, you write with images and dialogue. And unless you use voiceover, you cannot enter the thoughts and reflections of your characters.”

Coixet similarly underscores that a screenwriter must “capture the essence” of the story and characters via “cinematic ideas.” For example, on Un Amor, she says she incorporated “a thousand tiny, physical details” to get across ideas from the book, in addition to inventing character context not in the book.

Berger says the original graphic novel for Robot Dreams gave him “a road map with the basic storyline and structure,” from which he created new characters, settings and scenes — like a “jazz musician” riffing on the “melody” of the original. Although his film is very different from the book, he believes “the soul” is the same. “When I was working on this project, I really wanted to protect that, because the soul of the graphic novel is the reason why I made this animated film.”

Soler-Pont suggests genre-oriented thrillers and crime fiction are “co-existing” on page and screen in Spain with “arty, small, quiet stories.” “A request I’ve been receiving this past month is, ‘Do you have a book similar to 20,000 Species of Bees?’ ” (The critical and art-house darling from Spain premiered last year in Berlin, winning a Silver Bear for its 9-year-old star.)

Experts also see adaptations in Spain becoming more diverse and moving beyond the high-brow literary classics of yesteryear. “Despite the ongoing presence of Cervantes and García Lorca, cinema has moved away from the literary canon” popular for adaptations in the 20th century, and toward more recent publications as well as younger writers, says University of Salamanca history of cinema professor Fernando González García.

Fellow professor of film adaptation at the University of Málaga, Rafael Malpartida, who edits an academic journal focused on the interchanges between film and literature, points to the same trends of “de-canonization” and diversification of literary sources, as well as “self-adapting” by “playwrights who practice cinema” and “filmmakers who practice dramaturgy.”

This “crossroads of writings and crafts” has “never been so fruitful in the history of Spanish literature and cinema.” A phenomenon he highlights is that sometimes the film version is the only lasting artifact of an original play that was never published and is no longer performed. This means “the logical sequence between written text, represented text and filmed text from a script has been broken.”

For Soler-Pont, too, the past few years have brought a “fascinating dialogue between literature and screens. I have this feeling that nobody is writing a novel now without audiovisual or film references, so writers are changing their way of writing more and more. And in the film industry, people are reading a lot. I’ve never had more interesting conversations on literature than the ones I have been having with producers.”