This article is part of the special report of the Belgian EU Presidency..

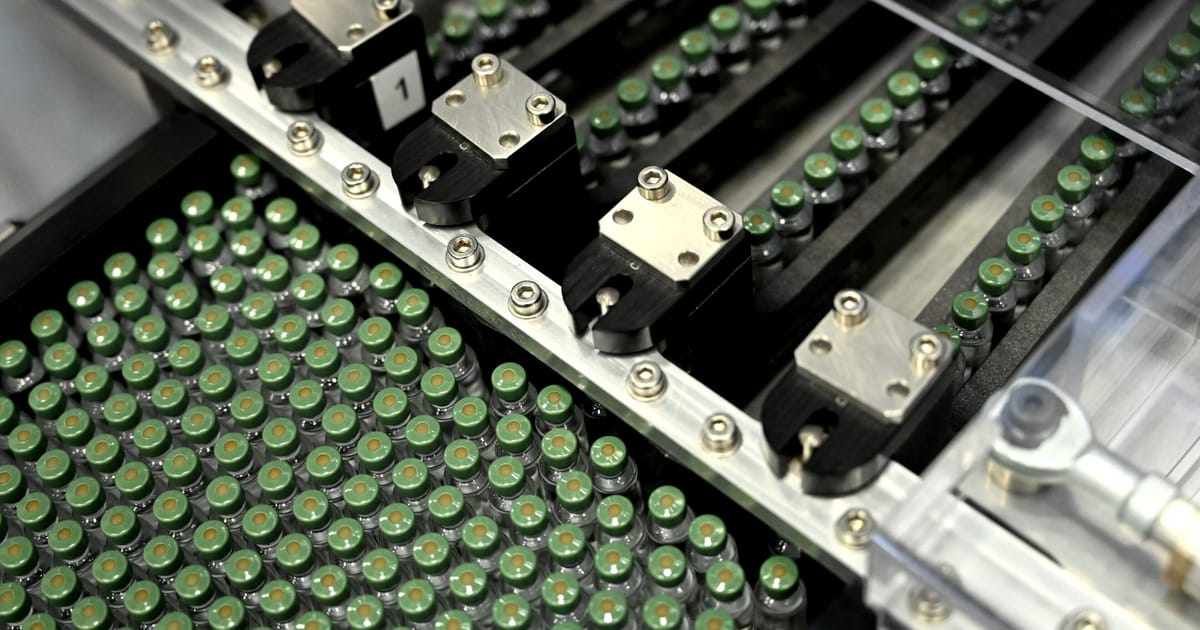

In the Austrian mountain town of Kundl, 10 fermenters with capacities up to 250,000 liters are bubbling with the continent’s pharmaceutical future.

The new factory, opened by pharmaceutical company Sandoz on November 10, will bring more than just jobs and money to Kundor. It will also increase the scale of antibiotic production in Europe.

“This site has the capacity to produce a minimum of 4,000 units.” [metric] Large amount of active pharmaceutical ingredients [annually]” explained site director Hannes Werner. Although aimed at international markets, this would be enough to cover all of Europe’s demand for amoxicillin, the most common form of the antibiotic penicillin.

The factory is an early green shoot in an EU-wide attempt to revive Europe’s once-dominant drug production industry. According to an analysis by the bank ING, the European Union is currently able to meet only a quarter of its own demand for off-patent medicines. The rest needs to be imported.

Europe relies largely on Chinese distributors for its antibiotic supplies, a situation that worried the Austrian government. So in 2019, it promised Sandoz a 50 million euro subsidy. In return, the company built a state-of-the-art antibiotic facility that can handle all production in-house.

The end result is a reduction in carbon emissions equivalent to 12,000 homes per year compared to the previous process, as well as high-quality EU-sourced antibiotics. Now European leaders want to replicate this across the EU.

Belgium will promote this in its next EU Council Presidency.

take home

The factory is part of a broader trend toward a return to pharmaceutical production, driven by a perfect storm of political, health and security concerns.

First, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has seen a scramble for limited vaccine doses and the withdrawal of critical medicines after India threatened to halt exports of paracetamol. Concerns about dependence on EU countries soared. And last winter, EU countries scrambled to deal with widespread shortages of over-the-counter medicines.

At the same time, rising geopolitical tensions have put a spotlight on Europe’s dependence on external suppliers for critical technologies such as microchips.

Belgium was the first country to promote the inclusion of pharmaceuticals among its critical technologies. The majority of EU countries quickly got on board, calling on the European Commission to take action.

It was an obligation. In October, the committee announced plans to create a Critical Medicines Alliance by 2024, with the aim of identifying the most vulnerable medicines that could benefit from additional measures to strengthen supply. . He also said that he is considering using subsidies to promote local production.

Belgian Health Minister Frank Vandenbroucke said at the POLITICO Health Summit last month: “The fact that the European Commission considers the European production of old basic medicines to be a matter of general public interest is a complete paradigm shift. “This represents an important new milestone.”

new resources

The problem is that there is one major reason why factories left Europe in the first place: money. Rising labor and operating costs, as well as stricter environmental regulations, mean it is more expensive to manufacture medicines in Europe than, say, in Asia. Without public funding, the Austrian factory would not have survived.

Subsidies are prohibited within the EU to avoid unfair competition. But these rules more frequently than ever apply carve-outs to investments in strategic industries such as hydrogen, semiconductors, and now, crucially, pharmaceuticals.

The European Commission’s October announcement clarified how state aid for medicines would work in practice. Important Projects of European Common Interest (IPCEI) is an available tool. These enable subsidies for innovative new technologies and are already being used.

Another tool could emerge that focuses on production research and development of unbranded medicines, the committee noted.

Additionally, there is an instrument called General Economic Benefits (SGEI), through which governments pay providers, such as post offices and public transport, to operate services that are not economically viable at market rates. can do.

A European Commission official, who was granted anonymity to speak freely, said SGEI could help ensure EU member states have access to medicines in emergencies. Once the standards are agreed, “member countries will be able to go to the market and say, ‘Look, we want the capacity to produce such and such medicines,'” the official explained. This establishes a production line that would otherwise be economically unviable.

But Europe is not the only region that can subsidize drug production if it wants to. And you may not even have the deepest pockets.

India, for example, has announced more than $1 billion in government investment to boost domestic drug manufacturing, but Sandoz’s global business director Ian Ball says this compares favorably with previous EU efforts. The difference is an order of magnitude.

The United States is also participating in the race for re-landing. On November 27, US President Joe Biden invoked the Defense Production Act, which allows states to intervene in economic policy on national security grounds, in order to manufacture more essential medical supplies in the United States.

green, clean and expensive

But the EU doesn’t just want production closer to home. We also want to reduce damage to the environment. For example, it is cracking down on polluting chemicals such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

In that regard, French pharmaceutical company Seqens announced in 2020 that it will build a new paracetamol production plant in Roussillon. Scheduled to begin commercial production in 2026, it will produce 15,000 tonnes of paracetamol’s active ingredient per year, enough to meet half of Europe’s demand.

The company’s general secretary Gildas Barrere said the use of the new technology could directly reduce carbon emissions by 75 percent compared to traditional processes.

Like the sand factory, Sequence’s facility also receives government support, covering 30 to 40 percent of the investment.

But regardless of whether there are such subsidies, medicines produced in the EU will simply be more expensive than medicines produced in Asia, where such environmental protection efforts are not taken into account. .

With these concerns in mind, “you can’t get a life-saving drug for less than a cup of coffee,” Sands-Ball told POLITICO.

Despite signs that pharmacies, hospitals and other purchasers are beginning to consider carbon emissions and security of supply in their purchasing equations, price is paramount.

The European Commission plans to remedy this problem with new procurement guidelines that take into account a wider range of factors, including environmental impact and supply chain safety. But for economically strapped European governments, medicines cheaper than coffee are a godsend. How much it intends to invest in local supply chains remains an issue that Belgium will have to address during its Council Presidency.