Coroners who conducted inquests into sudden and suspicious deaths in 19th century Ireland were viewed with contempt and scorn in a highly politicized and deeply divided society.

The inquest sheds new light on the nature of community life, revealing to the public the injustice and corruption at the heart of county society, the impact of poverty on the area, and preventable deaths during the Great Famine. .

The men who played the role of coroner in 19th century Ireland represented governmental authority and the need for social order and justice, but in a politically polarized society, local elites and communities There were often conflicts.

This book provides a history of the coroner’s role and features the inquests of William Charles Waddell (1798-1878), who served as coroner for County Monaghan for more than 30 years. It situates Waddell and the investigation into his death within the fabric of local government and Monaghan society.

autopsy

The coroner’s main duties are to investigate the cause and author of sudden, violent, and other unnatural deaths in the community, and to investigate debts and unpaid debts if the person responsible is found guilty of murder in a court of law. The purpose was to collect.

The inquest was open to the public and its purpose was to establish whether a crime had been committed. Once the coroner was notified of the death by local officials, an autopsy began and doctors, witnesses and jurors were summoned.

Bodies were often placed in the place where they were discovered or in a local public building. To reach a determination as to the cause of death, the jury evaluated witness testimony and a medical evaluation of the corpse.

Coroner’s reputation and authority

“Sir…the fact is that the Coroner in Ireland is (generally speaking) the meanest and most despicable person.” – Reverend Peter Brown, Dean of Ferns, Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany , June 7, 1819

[The disgrace] About the current autopsy system [is] It’s a terrible burlesque of jurisprudence. ” – Sir Dominic John Corrigan, Physician, September 9, 1840

In pre-famine Ireland, there was a general distrust of the coroner’s authority in investigating sudden, suspicious, or violent deaths. They are paid fees and expenses for each autopsy, and as another means of compensation they collect deodans (especially things that are confiscated or given to the Crown by law, objects or tools that are forfeited for causing the death of a person). I was able to do that.

As a result of this form of payment, they developed a reputation for being seen as “profiting” from death. The prevailing belief was that people in Irish local government were abusing the system to support their own politics and interests, and that many citizens were concerned about how revenue was being spent and diverted.

Coroner’s Religious Composition

Before the Poor Law of 1838, the coroner was the only elected official in local government. There may be around 100 people, more or less, who hold the role of coroner across Ireland. These were most often men with no professional qualifications and were landowners who hoped to gain or maintain the status of “gentleman”.

Within the comfortable monopoly of local government, the coroner’s role became a potential threat.

On June 25, 1823, Radical MP Joseph Hume (1777-1855) read out a list of offices and posts in which Catholics were underrepresented in the House of Commons. Only 29 of the 108 county coroners were Catholic. Still, the county coroner’s office had the highest percentage of Catholics of any position in government, at 26.9 percent. This shows that Catholics had a role in improving their social status.

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl of Grey, (1764 – 1845) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 22 November 1830 to 16 July 1834. alamy stock photo

alamy stock photo

However, coroners in Ireland were primarily Protestant men who shared a religion with others in the local authority, thereby contributing to increased homogeneity. Catholic coroners may therefore have suffered from prejudice from local Protestant elites.

witness fear

Evidence shows that people serving as witnesses and jurors in coroner’s courts were sometimes in danger and intimidated. In an impassioned speech in 1833,

Prime Minister Earl Gray (1764-1845) conveyed his shock at the brutality of men to Catholic juries and witnesses, and gave an insight into the pressures placed on coroner’s witnesses when they took part in an inquest.

Gray tells the story of a man who witnessed his father-in-law’s murder, but who sent a message saying, “I cannot do it myself, and I would sooner submit to the penalty imposed by the law than appear as a witness at an inquest.” Told. That is, without finally losing his life for the revenge of those who killed his relatives. ”

William Charles Waddell (1798-1878)

Waddell was of colonial Scottish Presbyterian descent and made a significant contribution to the social, political and economic history of County Monaghan. He owned and resided in his family’s ancestral home, Lisnaveen House, worked as a land agent and merchant, and also acted as an elected Poor Law Guardian, serving in various communities. Contributed to society.

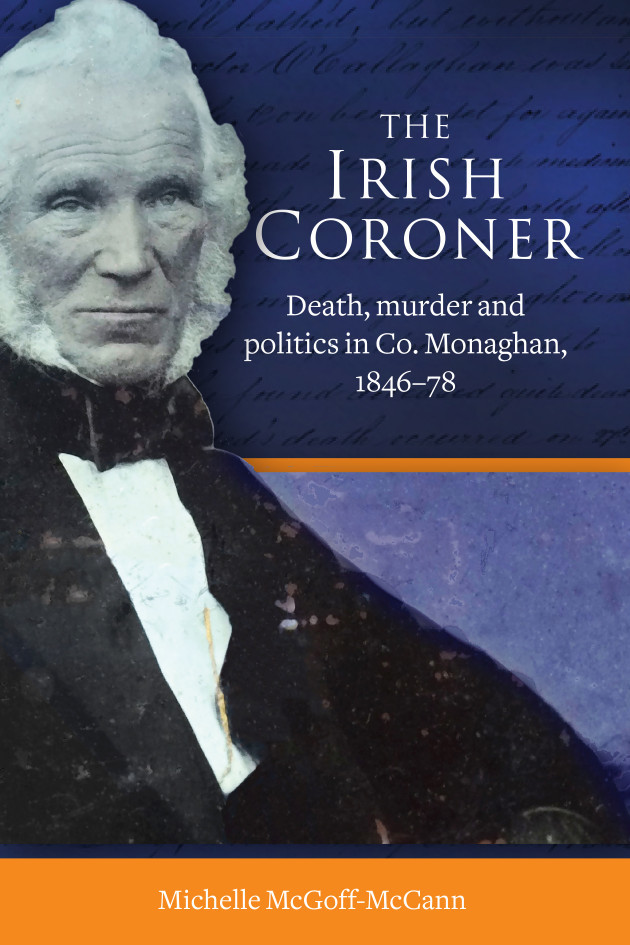

Rose Sweney May Inquiry, 1847. Four Court Press

Four Court Press

He was part of a new generation of middle-class professionals who used patronage, social networks, determination, and hard work to advance their social status. In April 1846, Waddell secured the position of coroner for County Monaghan, but just as Ireland was enduring the perilous years of the Great Famine, Waddell used his patronage network to secure the position. There is no doubt that he did so.

The role of the inquest during the Famine (1846-1852)

“How is it that the Grand Inquisition of the State has never investigated the deaths of thousands of people?” – Isaac Butt, April 1847

In July 1846, the Whig Liberal government of Lord John Russell (1846-1852) made dramatic changes to the policies introduced by his predecessor, Sir Robert Peel.

Lord John Russell in the House of Commons, 1832. alamy stock photo

alamy stock photo

They had a strict philosophy of not interfering with markets and food pricing. They allowed food warehouses to operate until empty and cut subsidies to support relief. During the last few years of Mr Russell’s leadership, public inquiries have uncovered unnecessary and preventable deaths and revealed inadequate relief policies for society’s poorest people.

Irish national and local newspapers published inquest verdicts that reflected negative public opinion towards government policies and demonstrated how inquests were used as a forum for the ‘voice of the people’. In January 1847, the nationalist newspaper the Limerick and Clare Examiner reported the results of a coroner’s inquest at a workhouse in Galway:

“It is found that the deceased Mary Commons died from the effects of starvation and destitution due to want of the necessities of life…I find that the said Lord John Russell and the said Lord Randolph Louth are guilty of manslaughter. Okay,” about the aforementioned Mary Commons.

Law, politics, and ideology worked against society’s poorest members, as an analysis of coroner’s inquests during the famine period of 1846-1852 shows.

Hunger in County Monaghan

In 1841, County Monaghan’s population was over 200,000, with a rural density of 370 people per square mile, most of whom were landless workers. By 1851 the country had experienced a population exodus, the population had fallen to 141,00 people, over 10,000 homes had been lost, and the situation had changed greatly and dramatically.

“Excluding towns, Monaghan experienced the third largest rural decline in Ireland between 1841 and 1851, at almost 30 per cent.”

The deaths captured by Waddell’s inquest reveal the causes of poverty on a huge scale in County Monaghan. The inquests are studied chronologically, showing how the removal of relief supplies (such as soup kitchens) caused significant changes in the distribution of hunger and death, as well as price shocks, food shortages, increases in evictions, and Lack of employment and limited relief distribution all contributed to the deaths.

Among Waddell’s many inquests was the inquest of Rose Sweeney of Killycarnan, held in the parish of Tedavnet on 26 May 1847. Sweeney was a widow with four children to support, and had no means of support other than the charity work of his neighbors. She was receiving twice-daily rations at a soup kitchen, and her name was on a list for three people, but before her third ticket went on sale, she was given rations due to “extreme poverty”. has passed away.

Food rations were given to hungry farmers at soup kitchens. alamy stock photo

alamy stock photo

Under the Soup Kitchen Act, Sweeney was entitled to three rations a day, one for himself and one half ration for his children. This may explain why the inquest was held, as Mr Waddell would have suspected possible mismanagement or corruption on the part of the local board managing the soup kitchen.

years after the famine

The coroner’s role contributed to the decline in power of local elites that began during the famine and continued gradually over many years in post-famine Ireland. In the years following the famine, Waddell investigated institutional deaths in workhouses, prisons, and psychiatric hospitals, exposing local corruption and mismanagement by facility staff.

Evidence of wrongdoing or misfortune by agency employees (who often secured their positions through patronage or nepotism) led to their dismissal and embarrassment to local elites.

He condemned the deaths of infants in workhouses, infanticide in prisons, the mistreatment of mentally disabled patients by attendants, and the unethical behavior of facility leaders who directly contributed to the unfair treatment of inmates in prisons. We found evidence of the act.

The coroner’s office survived amid municipal reform and the dissolution of many other judicial offices. The judiciary used its power as a “means of intervention in political and economic life,” and participation in judicial office functioned as social conditioning for local elites.

Dr Michelle McGough-McCann is a professional historian, author and visiting fellow at Queen’s University Belfast. She is currently working on several new publications, including a unique one-volume set of the original autopsies of Coroner William Charles Waddell (1846-77), to be published by the Irish Manuscripts Commission. I’m here.