Scientists working at Novo Nordisk’s research campus in Marof, Denmark.Credit: Carsten Snejbjerg/Bloomberg via Getty

The success of Denmark’s life sciences research sector can be attributed, at least in part, to a single event that occurred on the other side of the world more than a century ago. In 1921, three Canadian scientists, Frederick Banting, Charles Best, and John Macleod, extracted and purified the hormone insulin from the pancreas of dogs. Shortly thereafter, Danish couple Marie and August Klov, the latter of whom had just won the 1920 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on blood flow regulation, visited Canada and learned of this result. They sought permission to introduce the process in Denmark and began manufacturing insulin through the pharmaceutical company Nordisk Insulin Laboratories.

Buoyed by the commercial success of insulin as a treatment for diabetes, Nordisk Insulin Laboratorium merged with another company, Novo Therapeutisk Laboratory, in 1989 to form Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk. It also marked the launch of the Novo Nordisk Foundation, one of the wealthiest foundations today. Charitable Foundation of the World. The foundation is responsible for investing a significant portion of Novo Nordisk’s huge profits from several blockbuster drugs related to diabetes and hormone regulation in Danish research. In 2022 alone, it awarded nearly 7.5 billion Danish kroner (US$1 billion) in funding for new research initiatives. Many of Denmark’s largest companies are owned by charitable foundations, and tax laws encourage investment in research. “Many of the major foundations have a strong interest in biomedical research and biotechnology,” says Paul Nissen, a molecular biologist at Denmark’s Aarhus University.

Rising Stars of Nature Index 2023

The Danish government also invests heavily in research and development through funding for the academic sector and the Danish National Research Foundation. Established by the Danish parliament in 1991, this independent research funding body funds nearly US$70 million in basic research each year, more than a third of which focuses on life sciences. . There is also considerable foreign investment. 28% of people employed in Denmark’s life sciences sector work for foreign companies.

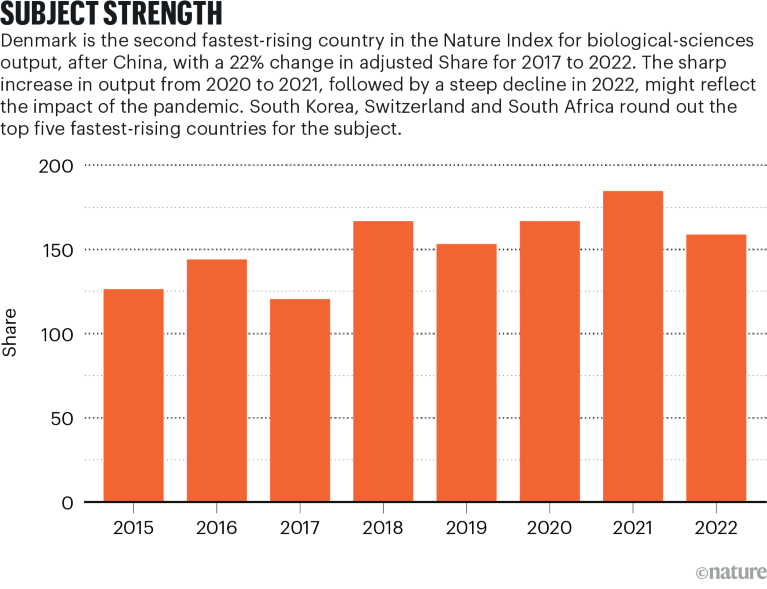

For a country of 5.8 million people, this combination of private and public support means significant research funding. This is a key factor in the continued success of the Danish life sciences sector, with high-quality research output accelerating in recent years. The Nature Index ranks Denmark 16th overall in bioscience production in 2022, making it her second fastest-growing country in this field after China. Denmark’s adjusted share, which takes into account annual fluctuations in article volume, increased by 22% from 2017 to 2022, outpacing South Korea (14%) and Switzerland (6%).

According to Bente Storknecht, dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark’s achievements in insulin production laid the foundation for Denmark’s strength in many other areas of life science research. “I think it has something to do with tradition,” she says. “In Denmark, we are rather proud of this in our life sciences research and industry.”

One such area is metabolic hormone research. In 1986, diabetes researchers at the University of Copenhagen, Jens Joule Horst, discovered GLP-1, an intestinal hormone that stimulates insulin secretion in the pancreas. This led to the development of a new class of drugs known as GLP-1 agonists, manufactured by Nordisk and other Danish pharmaceutical companies. Denmark’s researchers and pharmaceutical sector continue to build on that legacy with the development of several blockbuster diabetes and obesity drugs, including Ozempic, which provides potentially life-saving weight loss benefits for patients ( (see S. Sidik) Nature 61919; 2023).

Denmark is also making a name for itself in protein chemistry. For example, the Novo Nordisk Foundation Protein Research Center at the University of Copenhagen is a world leader in the field of proteomics, the large-scale study of protein structure and function. Since its founding in 2007, the center has identified more than 14,000 proteins using proteome sequencing. Characterization and study of these proteins has provided insights, including key proteins involved in the development of fatty liver disease (L. Niu) other. Mol. system. Biol. 15, e8793; 2019). “The handling and use of proteins as therapeutic agents is a very strong element that connects Denmark’s basic research and tradition to today’s industry,” says Nissen.

new insight

Denmark’s abundant research funding is a major advantage for the life sciences sector. But it also presents unusual challenges in deciding who, where, and how to use it. “As scientists, we of course want our money to be spent on basic research that everyone can apply for,” Nissen says. But he added that if the Nordisk Foundation gave all of its funding to basic research, “that would only overheat our research economy.”

The shift toward projects aiming for real-world impact was partially driven by the recognition that funding needs to be balanced at every stage of the pipeline, Nissen said. Novo’s translational research into health and disease benefits large mission-driven centers such as the Nordisk Foundation Protein Research Center.

Source: Nature Index

The focus is also on expanding the pool of researchers in Denmark who can invest this funding. In 2019, the Danish government prioritized ‘internationalization’ in its efforts to improve its innovation system. In addition to the wealth of funding available from the foundation, Denmark’s focus on internationalization makes it an attractive destination for international students and researchers, Storknecht said. Higher education in Denmark is free for European Union (EU) students or students on exchange programs, and government scholarships are available for non-EU students.

For researchers, Stollknecht highlights the BRIDGE program, a two-year postdoctoral fellowship in translational medicine funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Fellows are supervised by researchers from the University of Copenhagen, as well as industry and hospitals. Since 2014, the University of Copenhagen has doubled the number of foreign researchers, Storknecht says. One-third of the institution’s doctoral students and 60% of its postdoctoral fellows are international.

In 2021, the Danish government announced a new life sciences strategy aimed at improving conditions for research and development, including using health data and building more sustainable health systems. The strategy follows a sharp increase in interest and investment in building Denmark’s clinical trial capacity over the past decade, said Mark, head of clinical trials and pharmaceutical manufacturing policy at the Danish Pharmaceutical Industry Association, an industry group. A certain Jakob Bjerg Larsen said: There is broad political and industry support for Denmark’s hospital system and strengthening public-private collaboration to facilitate the conduct of the large-scale trials needed to bring new treatments to market. One result of this effort is Trial Nation, an online database of clinical trials recruiting patients in Denmark. Founded in 2018, it provides information to companies looking for sites to conduct clinical trials, including access to resources such as hospitals, researchers, patient networks and biobanks.

The strong political support for life sciences research in Denmark bodes well for the field’s continued success, says Larsen. “This is an area that everyone supports and has the political will to develop new strategies,” he says. “This current positive environment will continue into the future.”