Horslips was the High King of Ireland in the 1970s. They traveled the country dancing, going from ballroom to ballroom, to the delight of a generation of young Irish people. They toured in a flashy white Range Rover, the only one in Ireland at the time. When word got out that the band would be passing through their hometown, teens gathered at intersections and waved as the band drove by in a white Jeep.

One night the band was on their way to a gig in Navan. They passed through the speed checkpoint at high speed. Because it was raining, the band’s singer and bassist Barry Devlin, who was driving, was unable to stop quickly enough.

He skidded to a halt and reversed back into the barrier. Garda told him: “You were going a little too fast there, weren’t you?” “Officer, we were late for the concert.” “Oh, you’re in a band, right?” “Yeah.” The Garda looked inside the jeep and said, “ What band are you in?” I asked. “We are Horslips,” Devlin said cheerfully.

Garda stared at him for a moment, then shot back. “You may be Horslips, but we’re Fuzz. Look.”

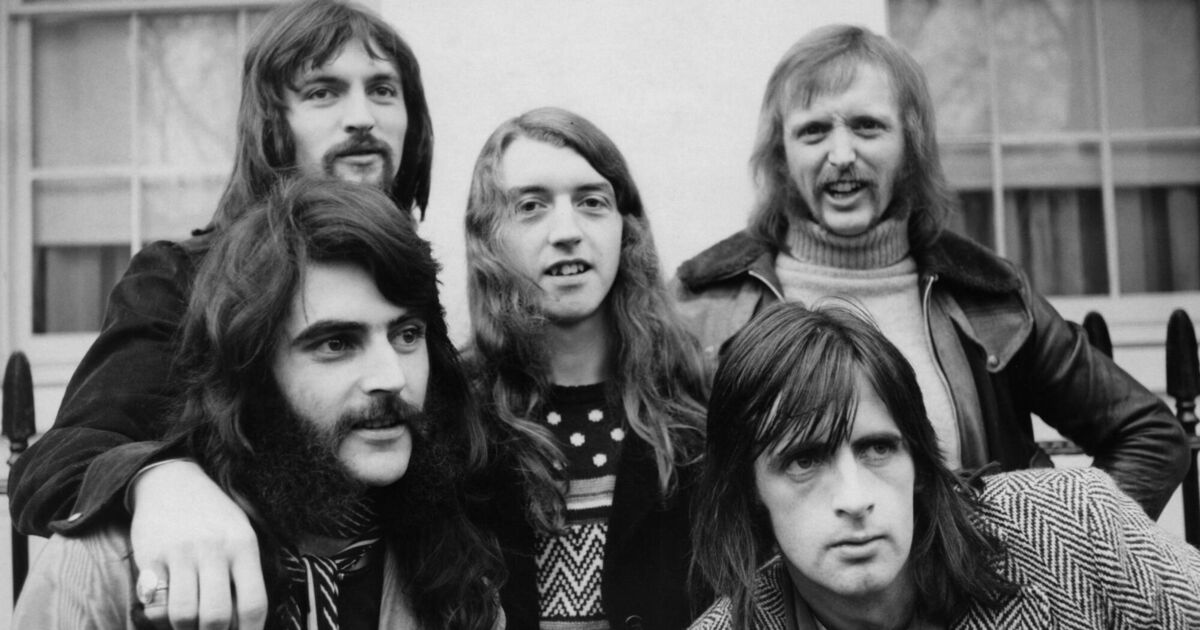

Horslips was formed in 1970. At the time, Devlin, Charles O’Connor and Eamon Kerr were working at Ark, an advertising agency in Dublin. They were fooling around by playing rock bands and imitating the playing of instruments in TV ads for Harp Lager, and they loved it so much that they thought it would be a challenge to form a proper band. Ta.

Jim Lockhart participated in the filming as a keyboard player. Incidentally, U2’s future manager Paul McGuinness appeared as an extra in the ad. The line-up was then completed by the addition of talented trad musician Johnny Fean. They called themselves the Four Poxmen of Horslips, an imitation of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, shortened to Horslips.

In 1972, Horslips released their debut album, Happy to Meet – Sorry to Part. They really didn’t want to spend another two years making their next record. They scoured for material, repurposing the atmospheric “doodles” they had created several years earlier as background music for an unperformed Irish-language production of The Tyne, a famous legend of early Irish literature. They saw The Táin, an epic story based on the concept An Tá in Bó Cúailnge (The Coolie’s Cattle Raid), the template for his album.

“By the end of 1972, concept albums had been in vogue since, say, Sgt Pepper’s and The Who’s Tommy,” says Eamon Kerr. “The idea of creating a bunch of songs around a storyline like The Táin made sense. Irish children were familiar with Irish myths and legends. Most of us were Christian Brothers. Everyone knew about it because they were experiencing it. [O’Connor grew up in Middlesbrough, England.] The key was finding a narrative arc that condensed a big myth like The Táin into two parts, a double-sided vinyl album, and breaking it down into a series of songs.

“What are you talking about? There was a quarrel over a bull. “Champion and Seven Sons came to take away Don.” To me, it was like something out of Homer. I read somewhere that “Tyne” is the equivalent of “Aeneid” in Ireland. The light bulb went out. It was a lot of fun.

Thomas Kinsella’s version of The Tyne was popular in Ireland at the time, but strangely I found Lady Gregory’s version to be more appealing. It has become more romantic and colorful.

“I wrote liner notes explaining the storyline so that someone who played the record to Scunthorpe, for example, could scan it and understand what it was about. There was no mention of Homer or anything like that. It was all Stan Lee and Marvel Comics! I didn’t say anything to the band because I didn’t want them to think I had ideas beyond my position. It’s because of it.”

The band recorded this album in 1973 in two studios, one in Kent called Escape. Jeff Beck – “I was into hot rods at the time. It was a lot of fun,” says Carr, who lived next door. They then did a lot of overdubbing and vocals at Richard Branson’s Manor Studios in the Oxfordshire countryside. Mitch Mitchell, drummer for the Jimi Hendrix Experience, came to the studio and sat there for a few days.

Teenage Mike Oldfield was also busy using the studio during his downtime to record his classic album Tubular Bells. As a result of their efforts, Horslips created their own iconic album. The album includes the timeless riff of “Dear Doom,” which was released a few years later as Larry Marin Jr.’s World Cup song, “Put ‘Em Under Pressure.”

“This riff comes from O’Neill’s March,” says Devlin. “The Chieftains, among others, played it. It’s a very primal noise. What Johnny Fean did was to play this song on guitar the way only Johnny would play a guitar, so the syncopation and the weight of the sound became tingly. -It was much more rock-influenced than when it was played on whistles. Now it’s a table-top song at weddings.

“In a way, Dearg Doom never really exported well. It’s very Irish. It’s in our DNA. We couldn’t reconcile it. We borrowed it. That’s a polite expression, which is part of the reason why it’s such a famous song and why it formed the basis of the Italia 90 football anthem.

“RTÉ Radio’s John Kerry tells a story about how, as a teenager, he offered to kiss a girl if she played him ‘Dearg Doom’. He was able to pull a tin whistle out of his pocket – which was pretty much all he took out – and he played “Dearg Doom” and he got a kiss. ”

The album cover artwork is impressive. It’s a close-up of a man’s fist, spray-painted silver and half covered in chain mail, that O’Connor picked up at an antique store and wore at a gig. He also has a square silver ring on his fist that his girlfriend from art school made for him.

For the logo, O’Connor created a papier-mâché head. When he photographed it, it looked like an ancient carved tombstone. This inspired Horslips fans to make five grotesque-headed marble dolls, totems the size of eggs, which he gifted to each member of the band.

“After The Tyne came out, we were in a bad car accident,” Kerr says. “We drove on. This guy came around the corner, drove on the wrong side of the road, and hit us head-on. Both cars were totaled. The poor man was killed. I was knocked out and lost consciousness. Our manager broke his leg and Axel tripped. Charles broke his nose.

“A monk who was transcribing oral stories that had been passed down through the centuries wrote that he had no idea what he was dealing with, whether these people were angels or demons. I read it in one of the manuscripts, and it should be done.” If this story is not told accurately, it will be a great curse to those who told it.

“Anyway, the album came out and there was a huge response. We were reeling and aware of this curse. Then we had this deadly crash. I remember being on a narrow road in the state. Barry Devlin was making all sorts of oaths. He took a little totem head out of his pocket and threw it about 100 yards across a ditch and dumped it in a field. I did.”

The album entered the top 40 of the UK album chart. “Dearg Doom” reached number 1 on the German singles chart. The London Times named it the album of the year. By the end of the decade, Horslips had amassed his 12 albums and performed over 2,000 live shows. The band disbanded in 1980, but reunited in 2009 for a few more years of swan songs.

The band members made their mark in various fields. Carr was a poet and accomplished boxing writer who oversaw releases by Philip Chevron and other musicians for a prominent independent record label. Devlin is a screenwriter, graphic novelist, and has produced several of his U2 videos. Jim Lockhart was a radio and television producer, primarily for RTÉ, and along with Devlin created the theme music for Glenloe. Multi-instrumentalist Charles O’Connor continues to release solo work, including his recent album The Shell. Even after Horslips disbanded, Johnny Fean continued to be active as a musician in the trad world. Unfortunately, he passed away in April 2023 at the age of 71.

Perhaps what most characterized Horslips was their eccentric fashion sense. They rode the glam rock wave through his 1970s, shining rays of sunshine across Ireland’s gray skies with their ridiculous costumes. As Bono put it, Horslips was “the answer to the insecurities that plagued us at the time.”

“I always say there’s still a warrant out against us from The Hague for crimes against fashion,” says Barry Devlin. “They’ll show up at our door any time and say, ‘Okay, where are you?'” But, like an ax murderer would say, “Everyone was doing ax murder back then,” must be taken into consideration. Back then, Bowie wasn’t some skinny white duke. He was wearing something quite unusual.

“When we showed up in Rockcollie, County Monaghan, we looked like the pound shop version of Bowie, but people loved it. This infuriated the trad community more than the fact that we were messing with the song. The idea of us messing around with a song dressed like that was an eye-opener. Fashion was a big part of it. If we went to a Horslips show, we might get scandalized. No, you might enjoy it. It will be different than anything else you would have seen in the early 1970s.”

Charles O’Connor, who played fiddle and slide guitar in the band, designed their costumes. Scottish seamstress Jackie McNeill has made his dream a reality. Devlin was always on the hunt for the ugliest costumes. Their dress sense and long, messy hairstyles sometimes attracted unwanted attention, especially in West Germany at the time when the far-left Baader-Meinhof gang carried out terrorist activities.

“German police got it into their heads that Eamon Kerr and Jim Lockhart resembled members of Baader-Meinhof, the Royal Air Force and the Red Army faction,” says Devlin.

“They were arrested in Frankfurt, Berlin and Bremen. When the police arrested them and recognized them as young men from Kells and Dublin respectively, they asked for a photograph next to them. The back seat of a Volkswagen police wagon. So, a photo has been circulating of two young men smiling awkwardly and posing proudly with a statue standing next to them.”