In a report prepared by the Boston Consulting Group for the

Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise (NHO) in January, it became clear that

Norway is lagging behind other northern European countries when it comes to

emission cuts.

“We must change Norwegian society in a way that we have

never done before to reach our climate goals,” NHO chief Ole Erik Almlid

told national newspaper VG (link in Norwegian) and added that “the situation is

desperate.”

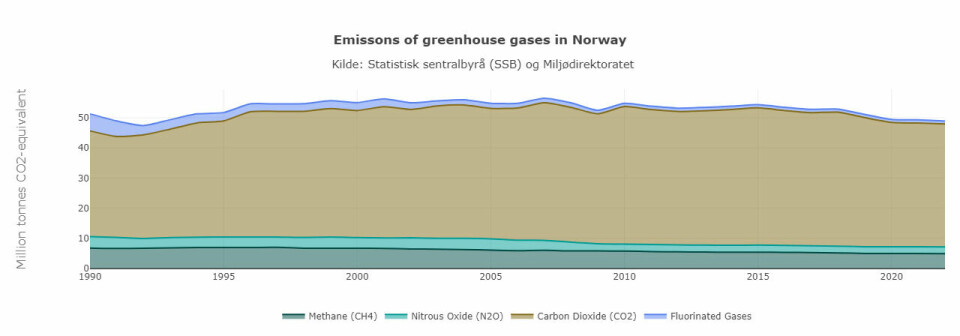

According to VG, Denmark, Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Finland have cut their emissions by between 35 and 49 per cent since 1990.

Norway has only cut 4.6 per cent, according to Environment Norway. This is despite the fact that Norway has a target of

cutting 55 per cent of emissions by 2030.

Have not tried

In Denmark, greenhouse gas emissions have decreased by 41

per cent since 1990. In Sweden, the decrease is 37 per cent.

Why hasn’t Norway achieved the same?

“Many people in Norway believe that no one can cut

emissions. But of all the wealthy countries in Europe, Norway is very special,” Elin Lerum Boasson says.

Boasson is a professor at the University of Oslo’s Department of Political

Science and a researcher at the CICERO Center for International

Climate Research.

“There are only a few wealthy countries that have not cut

emissions,” she says.

Boasson says there is no mystery as to why Norway is

lagging behind.

“We haven’t succeeded because we haven’t tried. That’s

the main explanation,” she says.

Have not had coal power plants to shut down

Stig Schjølset is chief adviser at Zero Emission Resource Organisation (ZERO).

He says that the main reason why Norway has cut

so little compared to Sweden and Denmark is that emissions from Norway’s oil

and gas sector have increased since 1990.

“It’s a uniquely Norwegian phenomenon,” he says.

The second reason is that Denmark had coal-fired power plants to shut down. Norway did not.

“We had 100 per cent renewable power production in 1990,

and we still have that. Denmark has gone from having 90 per cent coal to a

maximum of 10 per cent coal,” he says.

Wind power, bioenergy, and to some extent solar power have

largely replaced fossil sources for electricity production in Denmark, graphs from the IEA show.

Sweden had little fossil electricity production as early

as 1990, according to IEA data. Hydropower, nuclear power, wind power, and some

bioenergy are Sweden’s main sources of electricity.

No excuse

Has it been easier for neighbouring countries to cut

emissions than for Norway?

“It’s easier, of course, because climate policy in most

countries started by replacing coal or gas to generate electricity with solar,

wind, or other renewable sources. It’s the smartest and easiest thing for most

countries,” Schjølset says.

Sweden and Denmark also do not have a large petroleum

industry, like Norway.

But this does not absolve Norway from cutting emissions,

Schjølset believes.

“When you have an industry as profitable as the oil and

gas industry has been for Norway, you also have the financial resources to make

emission cuts in other sectors,” he says.

He thinks Norway has not made enough of an effort.

“Norway is one of the countries that really worked for

the 1.5 degree target to be an important part of the Paris Agreement. If you hold

that position internationally, then you also have to do much more to cut your

own emissions,” he says.

Energy efficiency and district heating

Elin Lerum Boasson has more to say about what lies behind

Sweden’s and Denmark’s emission cuts.

“Denmark has gone from having a real fossil power

industry to doing an incredible amount in energy efficiency and renewable

energy,” she says.

Sweden has managed to cut emissions from transport by

mixing in biofuel.

Biofuel is definitely one of the climate solutions we

need, according to Schjølset at ZERO. But experts disagree on how sustainable

this is in the long run.

The Swedes have also switched from oil heating and developed a lot of district heating for heating buildings.

Those who want to defend the low Norwegian cuts will say that it

has been very difficult for Norway because we had renewable energy in to start with, Boasson says.

“It’s true that most countries tackle the power sector

first. But that doesn’t mean that it has been very easy for these countries to

do so. It has cost a lot of money and political effort,” she

says.

Sweden is slowing down

Boasson herself is a member of the Climate Policy Council in

Sweden, which advises the Swedish government on achieving its climate goals.

“For the first time since climate change was put on the

agenda, Sweden now has a policy that means they will not continue to cut

emissions. There has been a dramatic change in climate policy with

the new government,” Boasson says.

Among other changes, this involves reducing the

requirement for blending biodiesel into petrol and diesel.

But the country is still well positioned, Boasson says. Emissions in Sweden fell by three per cent last year compared to the year before.

Difference in governance

Tor Håkon Jackson Inderberg is a political scientist and

senior researcher at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute.

He highlights climate policy management as one of the

differences between Norway, Sweden, and Denmark.

“I have previously criticised the structure of the

Norwegian Climate Act, for example, because it’s quite weak. It sets some

targets, but is very poor at sub-targets and the necessary structures that

would oblige the government to follow up on its own targets with concrete

measures,” he says.

Sweden and Denmark also have climate laws that legislate

emission cuts.

At the same time, they have stronger regulations, Inderberg believes. They also have independent climate councils that are supposed to keep the governments accountable.

Inderberg highlights the Green Book as a positive

development in the management of climate policy in Norway. The Green Book is a

kind of account that shows how Norway is doing in terms of meeting its climate targets, according to the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, NRK (link in Norwegian).

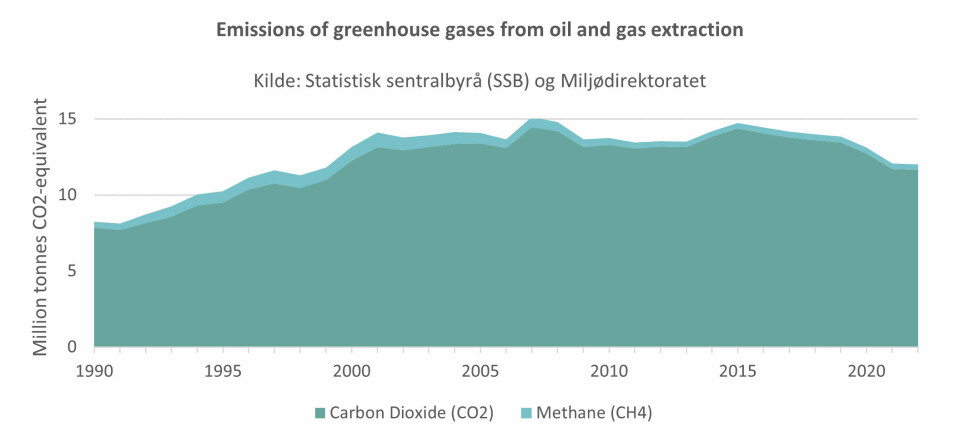

Large increase in oil and gas emissions

What’s behind Norway’s 4.6 per cent emission cuts?

The oil and gas industry accounts for a quarter of

Norwegian greenhouse gas emissions. Emissions nearly doubled from 1990 until

2007. Since then, emissions have decreased, but the overall increase is still 48

per cent since 1990, according to Environment Norway.

“The reason for this is mainly that we have invested a

lot and expanded a lot,” says Boasson.

And more energy is required to recover oil from ageing

fields.

Emissions have decreased slightly because a number of old

oil fields have been closed. Norway has also discovered gas fields that can

be developed with fewer emissions than oil, and several new oil and gas fields have

been electrified.

The Johan Sverdrup, Ormen Lange, Snøhvit, Troll A, Gjøa,

Goliat, Valhall, and Martin Linge fields all operate with land-based electric power,

according to norskpetrolum.no.

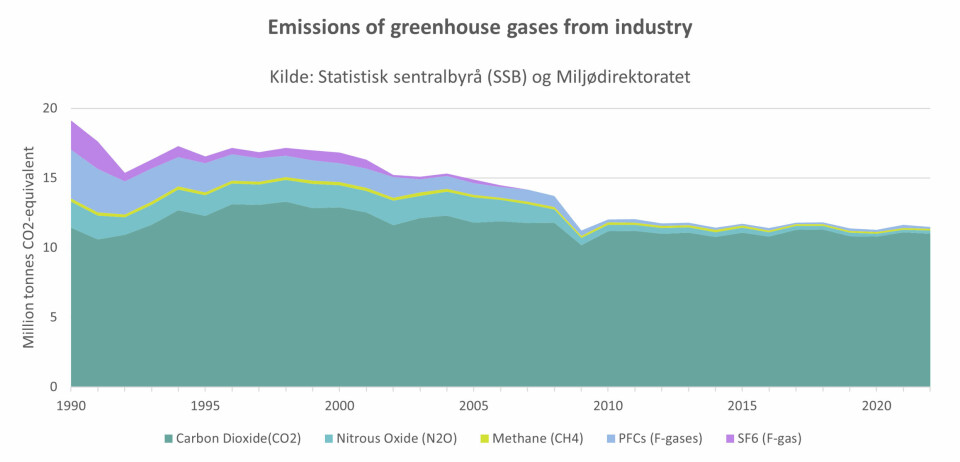

The industry has cut 40 per cent

Industry emissions, on the other hand, have significantly decreased: a whole 40 per cent since 1990.

“The industry has managed to cut greenhouse gases other

than CO2 through process improvements,” Schjølset says.

Emissions of the fluorinated greenhouse gases PFCs

(perflurocarbons), the greenhouse gas SF6, and nitrous oxide were reduced until 2010. CO2 emissions have remained stable.

“The next major action that Norway’s industry has to take

is to eliminate CO2 emissions linked to heating and other uses of

fossil energy in industrial processes,” says Schjølset.

Emissions from transport have increased a great deal since

1990, as in many other countries. Now it is levelling off, and emissions from

road transport will fall in coming years. This is due to the use of a biofuel mix,

and the fact that Norway is a leader in the adoption of electric cars.

Oil and

gas industry delays progress

Carlo Aall, senior researcher at the Western Norway Research Institute,

believes the oil and gas industry delays Norwegian

emissions cuts.

“It’s the biggest source of emissions,” he says.

Aall believes that clean electricity that could have been

used elsewhere will be used to electrify the oil and gas industry.

“You have to build cables and huge facilities. I

think that the more we bet on that horse, the more it will delay us, because it

requires an incredible amount of infrastructure,” he says.

Aall questions how wise it is to use resources to

electrify an industry that “we should really start to reduce”.

“To put it bluntly: When we have finally reduced

emissions from the production of oil and gas, we will no longer be able to sell

it,” he says.

Buying time by paying other countries to cut

Aall believes that Norway struggles with double

communication.

“On the one hand, there was rejoicing after the last

climate summit, because the final declaration finally said that we must start phasing

out the industry for oil and gas production. But that clearly does not apply to

Norway. The spilt only becomes more and more apparent,” he says.

Another reason Norway has made few cuts is an

ideology about cost efficiency in climate policy, Aall believes.

This is based on arguments that Norway can

cut more greenhouse gases by spending money abroad than in Norway.

“The supposed rationale behind this ideology is that we are buying time. While other countries made emission

cuts for us, our job was to develop technology in the form of battery-powered cars,

battery-powered airplanes, and carbon capture and storage facilities,” he says.

“But these technological efforts have been shelved. Now

all available domestic resources are instead being used to extend the fossil

era.”

Norway has become a world leader in adopting electric car

technology. But the country should have made

more progress with other measures, Aall believes.

2030 is fast approaching

Norway must cut emissions by 55 per cent of 1990 levels

by 2030.

According to the target that has been submitted to the

UN, these cuts must be done in collaboration with the EU. In other words,

Norway can pay for emission cuts in EU countries. The government has also set a

separate target for the cuts to take place domestically.

Boasson does not think that the government has presented a clear plan for how this will be done.

She is also not convinced that it will be possible to make

the cuts abroad.

“In this case, we have to find projects and countries

that are willing to let the Norwegian state finance emission cuts there and to

allow those emission cuts to be credited to Norway’s and not their own

accounts. It would have been nice if the Norwegian government told us about how

it is working to achieve these agreements with EU member states,” she says.

Doubt Norway will reach its goal

Tor Håkon Jackson Inderberg at the Fridtjof Nansen

Institute thinks things look bad for the 2030 target.

“I don’t think we will be able to make our goal. Either

you can cut significantly in petroleum, which doesn’t seem likely to happen, or you

have to electrify much faster. But the new stream of electricity we need does not seem to

be in place either,” he says.

Stig Schjølset agrees that Norway is not in a position to

achieve its goal. But he says there can certainly be emission cuts in the

future.

Industry could make big cuts quickly

“Emissions in the transport sector will continue to

decrease, because soon all new passenger cars sold will be electric. A larger

proportion of vans and lorries will be electric,” Schjølset says.

Industry could also make major cuts.

“The largest point emissions from industrial companies

account for a large proportion of the total emissions in Norway. Here, we can achieve big cuts through measures at quite a few facilities,” he says.

A report from the Norwegian Environment Agency (link in Norwegian) calculates that emissions from industry,

petroleum, and energy supply could be cut by 67 per cent from 2021 levels by 2030.

This would require 14 terawatt hours of renewable power,

some forest raw materials, and the storage of four million tonnes of CO2.

For example, the Norwegian gas plant on Melkøya in Northern Norway emits 800,000 tonnes of CO2, Schjølset says. If it

is electrified, 1.6 per cent of Norway’s emissions will be cut.

“Hydro and Yara could achieve the same. Many industrial companies are working with specific technologies and projects that

can reduce emissions almost to zero,” he says.

It will happen with time, Schjølset believes, but if it is to

happen quickly, something must change.

“With a combination of stricter state requirements and

support schemes, plus the policies we have today, many of the projects could be

realised around 2030,” he says.

In order to get enough electricity, the grid must be

expanded more, and Norway must increase the production of renewable power much

more, Schjølset adds.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no