When it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, there is a dynamic tension between the ambitious goals of the EU and its Member States, on the one hand, and the realities of embedded and entrenched elements of the economy, such as agri-food, on the other hand. The European Union set a goal in 2021 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by 50% by 2030. However, progress remains slow. Progress in agriculture is particularly slow. Rasmus Larsen sheds light on the situation in Denmark, one of Europe’s centers of intensive farming. A new three-way partnership is being proposed in Denmark after a series of misfires. What is this? Will it work?

Climate change mitigation in agriculture and its dissatisfaction

The European Environment Agency (EEA) highlighted this issue in June 2022, stating:

“While emissions are decreasing in almost all sectors, especially energy supply, industry and the domestic sector, emissions from transport and agriculture are not decreasing at a sufficient pace. In fact, emissions from agriculture has recently increased” (EEA, June 2022).

Another recurring theme in the EU’s climate parliament is the 2025 milestone, which serves as the first benchmark for assessing or achieving specific reduction targets. As this deadline approaches, the need for urgent action becomes increasingly apparent.

In response to this urgency, a group of experts commissioned by the EU published a report by Trinomics/IEEP in late autumn last year entitled ‘Pricing agricultural emissions and challenging climate change mitigation in agricultural and food value chains’. published a book. (Trinomics/IEEP report)

Read/Download – Pricing Agricultural Emissions and Rewarding Climate Action in Agriculture and Food Value Chains (2023)

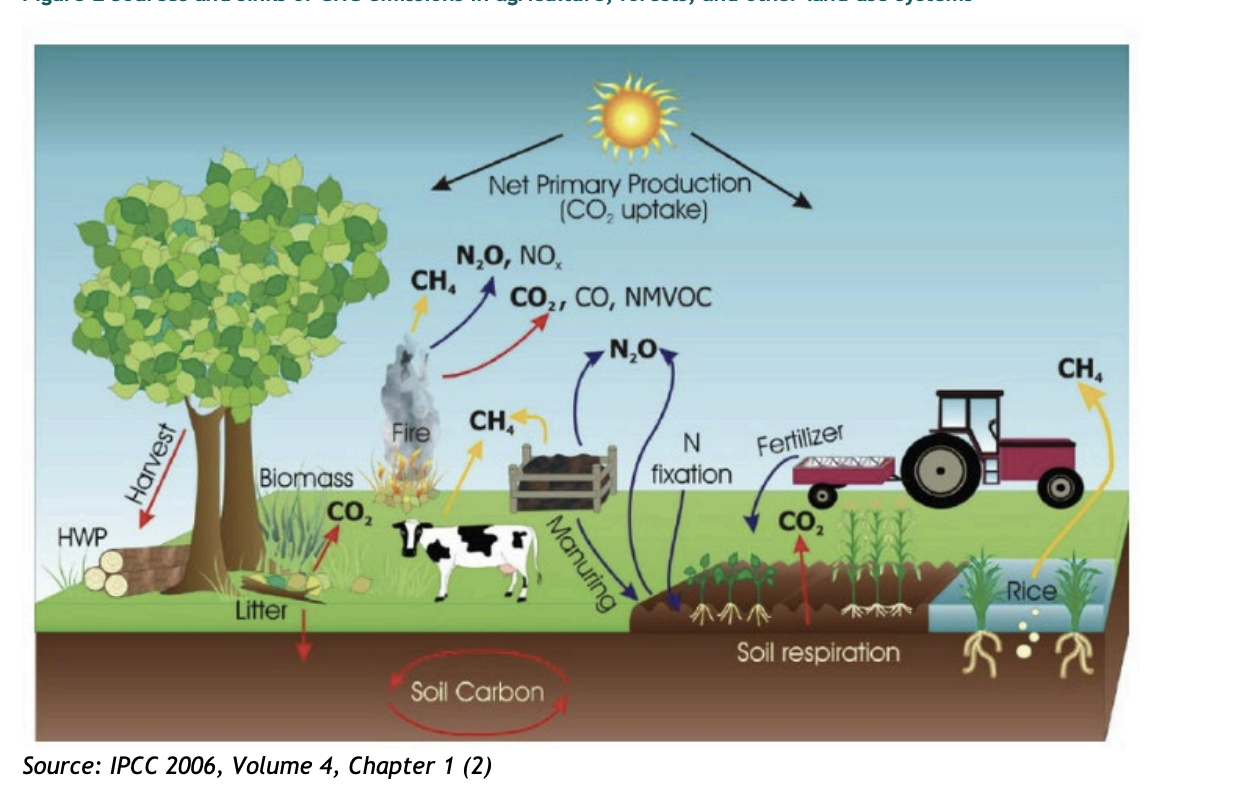

The report reveals that almost 80% of GHG emissions from European agriculture come from enteric fermentation, a process that occurs in animals’ digestive systems. Specifically, livestock in Europe generates 182.5 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year.

The first section of the report focuses on identifying “polluters”, with “upstream” sources (such as fertilizer producers) and “downstream” polluters (meat plants, burger bars, and ultimately consumers) persons, etc.). The 322-page second part details the various emissions and data collection points, taxation options, and efficiencies and administrative burdens of Emissions Trading System (ETS) allocations. His emphasis on the ETS, which mirrors the quota system used in European industry, suggests that Brussels is leaning towards this approach.

The report ostensibly lays the foundations for legislative proposals for the EU’s 2040 climate target, which would reform European climate law. However, with EU elections looming and no common regulatory framework on agricultural GHG emissions in sight, this report is more important to Member States than as a blueprint for future legislation similar to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). It can serve as a source of inspiration and surprise for many people. ).

Despite the various strategies outlined in the report, the inevitable reduction of livestock appears to be a necessary step. This realization is beginning to emerge, albeit slowly and with difficulty, among countries with large livestock populations, such as Ireland, the Netherlands, and even non-EU member New Zealand. For example, the Netherlands plans to reduce livestock numbers by buying up and closing down farms (if not in too strong of a word), and this strategy was recently approved by the Danish Competition Commission, and the Allowed to use finances.

Denmark, with its large livestock population of 25 million pigs and 1.5 million cattle, takes a different approach. The Danish government is considering an indirect method, planning a yet-to-be-defined tax on CO2e emissions at farm level.

CO2 tax on agricultural production in Denmark

The introduction of a CO2 tax on agricultural production has been considered since the Climate Act of 2019, also known as the 70-30 Act. The law, named after the goal of reducing emissions by 70% by 2030, was signed by all major political parties in Denmark’s parliament, including those representing farmers. Despite this agreement, concrete action has been slow to move forward. Various expert groups, committees, and researchers have struggled to devise taxation models that are acceptable to the farming community. Meanwhile, the agricultural sector continues to receive significant funding to research technological solutions that can reduce emissions without reducing livestock numbers. Significant investments have been made in these so-called “technical mitigation measures.”

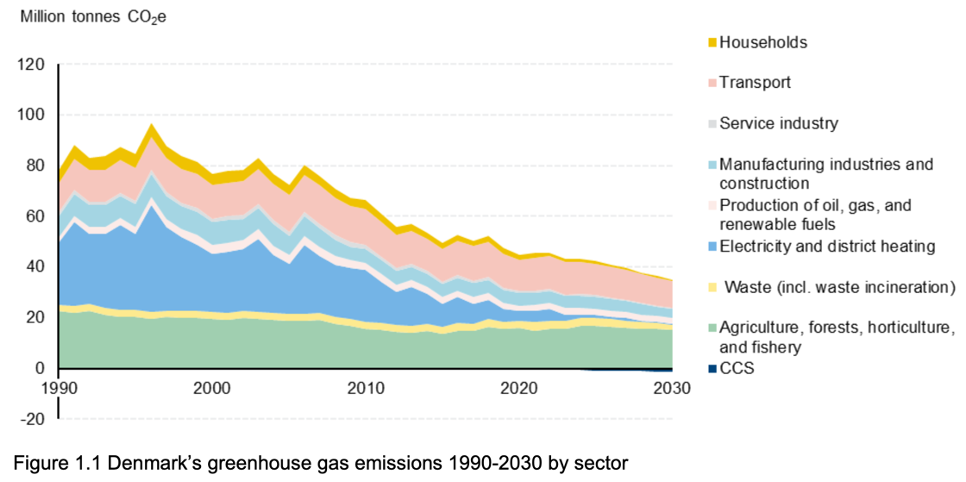

While other sectors are gradually adjusting and reducing their emissions, agriculture’s share of Denmark’s total emissions is on the contrary increasing. This increase makes it politically impossible to delay action on emissions from agriculture.

That was then, this is now

This situation influenced Denmark’s current political coalition. After the last election, the Social Democratic Party, despite having a centre-left majority, decided to join the right-wing Peasants’ Party (Van He chose to form a government with the government. Agricultural tax was included in the coalition government’s manifesto. However, despite some Venstre MPs joining the opposition in attacking the tax, the coalition’s political leaders acknowledged that the tax targets production.

However, as is often the case with agricultural regulation in Denmark, numbers and facts were debated by the agricultural lobby, leading to political hesitation and the appointment of a supposedly independent expert group to clarify the issue. ing. This process typically results in delays and unresponsiveness. In this case, the situation was further complicated by the introduction of unforeseen modifications to the original mandate two years into the expert group’s mandate. The amendment proposes to consider a consumer tax model, which is widely considered inefficient by economic experts because it fails to incentivize farmers to reduce emissions. It is a concept that The expert group chair’s dissatisfaction with this amendment was publicly expressed.

In contrast, the Danish Council on Climate Change (DCCC) presented a tax model for agriculture in February 2023 that garnered support from all stakeholders except farmers. The model, detailed in the DCCC report, suggests a carbon tax of DKK 750 (approximately €100) per tonne of CO2e, which would reduce emissions compared to 1990 levels if only existing technical measures are taken into account. It is possible to reduce the amount by about 45%. However, achieving the 55-65% reduction target for agriculture and forestry by 2030 will require a combination of new technologies and changes in production systems. The DCCC warns that focusing solely on technical measures could delay the green transition and lock the agricultural sector into carbon-intensive practices.

As a result of the amendment, the progress of the expert group was reset. But recently there have been signs of political determination to move forward. Venstre’s leadership acknowledged the impending tax, but was soon replaced by a new leader nicknamed “Tractor Troels.” Following this leadership change, the expert group announced that the deadline could not be met. To those unfamiliar with Danish politics, these developments may seem unbelievable.

Further complicating matters, a new scandal has emerged involving journalists seeking access to communications between the agricultural lobby and expert groups. The request was refused, violates norms under Denmark’s Freedom of Information Act, and is currently under investigation by the authorities. Danish Ombudsman.

and now?Let’s try a three-party partnership

So where are we? It is hard to say, but the current official forecast is that the expert group’s report will be published in early spring. The actual bill will then be drafted in a highly unusual “tripartite partnership” in which the agricultural lobby, green NGOs, and the finance and economy ministers, chaired by Tractor Troels, consult and agree. . and develop the specific language of regulations governing the tax. The work is estimated to be finished in June, and the tax ministry’s website says it is expected to be passed by parliament before the summer holidays without any public hearings.

If we look beyond our borders to Germany and the Netherlands, where recent attempts by governments to reduce agriculture-related greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants have been met with severe disruption and some frustration, Denmark ‘s “tripartite partnership” model has a certain logic. . It remains to be seen whether we will be able to meet our reduction targets within the next 12 months or beyond. .

*( Danish original: Endelig skal ekspertgruppen komme med forslag til mulige måder at konstruere kompensationsmekanismer, herunder blandt andet bundfradrag, tilskudsordnin-ger, Differentierede satser, forsinket indfasning og sammenhæng til eksisterende tilskudspuljer, Generelle til tag og andre murigue Herunder bør den store variations i erhvervsbelastning både mellem og in-den for sektorer (Forslag til kompens ationsmekanismer skal afvejes iforhold til øvrige effecter Heraf.)

Continue reading…

Steering ARC through the rough waters of 2024

EU digital agriculture needs a clear socio-ecological direction

Who provides the science and research for sustainable food systems?

Marburg Gathering | Building bridges to a future-proof food system

Who owns farmland in Denmark?