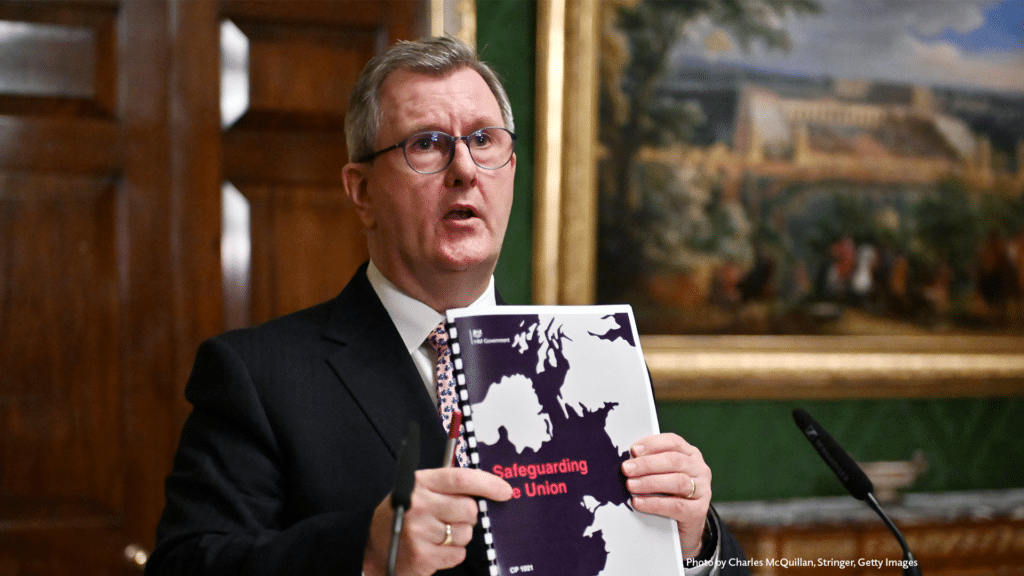

Details of an agreement with the UK government to return the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) to power-sharing in Northern Ireland have been published.

Joel Ryland analyzes the details of the Directive document and suggests that, while the changes to trade relations are fairly small, there are new commitments to strengthen Northern Ireland’s position within the Union.

When the UK Government published its “Protecting the Union” command document this week, much of the focus was on how it would significantly impact trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

The DUP’s main objection to the Windsor Framework was that exports from GB to NI would continue to be subject to paperwork and checks (albeit in a much more limited form than under the original protocol). DUP leader Geoffrey Donaldson’s claim that the new paper addresses these concerns dominated the headlines.

On closer inspection, the paper appears to do little to change trade relations and is primarily an exercise in rebranding the Windsor Framework.

However, this focus on the trade component hides some potentially important new proposals for the implementation of the framework that could meaningfully protect Northern Ireland’s place in the Union.

Returning first to trade, the key changes include the Windsor Framework’s ‘green lane’ (which simplifies paperwork and eliminates most inspections for shipments moving from GB to NI where there is ‘no risk’ entering the EU). Replace it with a new ‘Britain’. ‘Internal Market System’ (UKIMS).

Other than the name change, the differences are minimal. The rules for businesses to access his UKIMS are the same as for Greenlane, and the reduction in paperwork and product inspections may be minimal or non-existent at best. Green Lane operations depend on efficient and reliable data sharing, so there is a good chance that the EU will be concerned if the changes here are more significant than they initially appear.

Another change is that a wider range of goods (26 other world meat and plant products) will now be available for UKIMS, with some meat products now able to be imported directly into Northern Ireland on a UK basis. It is to become. , rather than the EU, tariff rate quotas (as expected in the original framework).

This will allow NI to take full advantage of UK trade agreements (e.g. liberalizing import regulations for New Zealand meat), but will also expose Northern Ireland’s meat industry to further competition from imports from other countries. They would not welcome being exposed.

Although less discussed, this document makes potentially more significant commitments to how the framework will be implemented in practice. These proposals are partly aimed at reassuring the DUP by reiterating existing commitments in the Framework, but there are also important new commitments that will strengthen Northern Ireland’s place in the Union.

For purely symbolic purposes, Mr Donaldson has put a lot of effort into the promised amendments to Article 7a of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, which will ensure that the Windsor Framework will be a part of Northern Ireland’s EU law. will be updated to recognize the constraints it imposes on dynamic coordination. This is just a repeat of what the framework already does.

Similarly, legislation is expected to be introduced that would ban the UK from entering into “future agreements with the European Union that would adversely affect the operation of the UK’s internal market”. A government with a decent-sized majority could lift this, but it is unusual for a British government to pay such explicit attention to the situation in Northern Ireland. Sometimes symbols are important.

And, more specifically, the paper provides clear details about the operationalization of the Stormont Brake, which would allow the NI Parliament to block the application of updated parts of EU law. Given that Stormont will need to monitor and assess wide-ranging EU regulatory changes, serious doubts have been raised about whether the brakes will work effectively in practice.

The document outlines that Westminster will notify Stormont in advance of relevant EU proposals and when the window to trigger the brakes opens. If implemented well, this could provide much-needed information to MPs to track EU-led disagreements, but the brakes (which would prove a significant impact on daily life) The hurdles for its use remain high.

And, perhaps most importantly, the document contains specific obligations for the government regarding disagreements with the UK-led NI. A bill will be introduced that would require ministers to assess whether the proposed legislation would have a negative impact on NI’s position in the UK domestic market. A new working group with NI executives will also be established to identify and address emerging concerns regarding the operation of the framework.

‘Britain in a Changing Europe’ A lack of consideration of how new legislation will impact on the UK’s internal market is a lack in post-Brexit policy-making, with GB and NI We have repeatedly argued that there remains the potential for major differences between the rulebooks. The command paper’s proposals have the potential to fill this gap.

For example, it could have required Westminster to consider whether reforms to gene-editing rules could allow British farmers to harm Northern Ireland farmers. and whether the new ban on animal testing licenses will impact the flow of cosmetics from GB to NI.

However, the main uncertainty with this proposal is that the Minister appears to have discretion over when such an assessment needs to be made. This means that in practice the obligation can be largely ignored.

Ultimately, therefore, the onus is on Westminster to deliver on the paper’s commitments. The UK government has repeatedly over-promised and vastly under-promised regarding Northern Ireland (“no border in the Irish Sea”). If we can break that cycle by diligently applying new, well-thought-out policies, we can build much-needed trust.

By contrast, the widely held view in Northern Ireland that the UK Government does not believe that Westminster will treat the paper as a mere letter to the DUP, and that the warm words will disappear as soon as power-sharing is restored. It is likely that it will simply become established. Mind it.

Until trust is fostered between Westminster and all communities and political parties in Northern Ireland (not just one), the newly revived NI executive will struggle to find equilibrium.

Written by Joel Ryland, Research Fellow in Changing Europe, UK.