The British Empire has left many horrific legacies across the world, but perhaps none as enduring, bloody, or self-defeating as partition. In its 20-century retreat from empire, the administrators of the British state repeatedly found themselves departing a land that had sharp ethnic, religious, and cultural divisions and figured the smart move was to draw a line on the map on their way out. It didn’t especially matter if the map was accurate or up to date. It didn’t particularly matter what might happen to the people who ended up on the “wrong” side of the border. Hardly considered was the possibility that decades and decades and decades of war would follow.

Ireland was divided into Northern Ireland and the Free State, leading to the decades-long war we euphemistically call “The Troubles.” India became India and Pakistan with a line drawn by Cyril Radcliffe, a man who had never been east of Paris, was given five weeks to do the job, and refused payment when he saw the mass death and displacement that ensued. (He still accepted a knighthood for it in 1948, though.) British Mandatory Palestine was to be divided into a Jewish state and an Arab state, with a shared Jerusalem. I can only assume that’s working out great.

But here’s something miraculous: in Northern Ireland, right now, there is peace. There are still ever-present tensions and setbacks and political gridlock, and occasional, horrible flashes of violence, like the murder of journalist Lyra McKee in 2019. But there is a peace, however imperfect—a peace that, not too long ago, would have seemed unimaginable. As unimaginable as peace in the Middle East.

No conflicts are perfectly analogous to one another, but there are, surely, insights to glean here—lessons about how paramilitary and state violence interact, about the role of the international community, about how to build a peace process. Instead, the Western world seems more interested in imperiling Northern Ireland’s miracle than trying to recreate it.

The simplest version of the story of what would become Northern Ireland begins with the Plantation of Ulster in the early 1600s. Scottish and English settlers were “planted” on land confiscated from Gaelic chiefs in Ulster, Ireland’s northern province. Around 20,000 adult male British settlers were living in Ulster by the 1630s, to which you would add their wives and children to get an idea of the total planter population. The settlers were all required to be English-speaking, Protestant, and loyal to the British Crown (though low take-up meant that wasn’t always the case). Centuries later, there are two broad groups in what is now Northern Ireland—the predominantly Catholic community who identify as Irish nationalist, and the predominantly Protestant community who identify as British and support the union with Britain. And so it’s easy to assume that the nationalists are indigenous and the unionists are settler colonialists.

The truth is a bit more complicated. Even if you don’t concede any land rights to people who have lived on the island of Ireland for nearly half a millennium, it’s impossible to cleanly trace unionists’ ancestry to the plantation. There has been continued migration between Scotland and the north of Ireland forever. The history of these two places is sufficiently intertwined that if you go back far enough, the word “Scot” literally meant Irish; in ancient times, we basically swapped countries. “The Scots (originally Irish, but by now Scots) were at this time inhabiting Ireland, having driven the Irish (Picts) out of Scotland.…” the spoof history 1066 and All That puts it, “while the Picts (originally Scots) were now Irish (living in brackets) and vice versa.” This intertwining is part of why the Ulster Plantation was more successful than the other plantations of Ireland. (The Munster Plantation—in Ireland’s southern province—in the 1580s failed to attract anywhere near the 11,000 plus settlers planned for.) While the Plantation failed to materialize the artificial, British-ized social structure that the Crown had envisaged, in the decades and centuries that followed, something more resilient took its place: an organic, British-identifying society, existing alongside and intertwined with the Irish nationalist one.

By the start of the 20th century, unionists made up about 25 percent of the island of Ireland, but were a majority in the northeast. Irish nationalists managed to get the British government to pass a Home Rule Bill, which was due to grant Ireland its own parliament with control over domestic affairs in 1914. There was fierce unionist opposition to Home Rule, including the setting up of the paramilitary organization the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) to resist its implementation. (The bill was put on the back burner with the outbreak of World War I, during which the whole Irish Question was radically altered by the Easter Rising and subsequent War of Independence.)

Home Rule, a popular unionist slogan went, would mean Rome Rule. Protestants would go from being part of a majority in the United Kingdom to being a small minority in Ireland, and feared what kind of laws a Catholic-dominated Irish parliament would pass. If this reaction might have seemed slightly hysterical at the time—and motivated in no small part by anti-Catholic prejudice—the subsequent century makes the unionists’ fears seem well-founded. When partition was implemented, it left the Irish Free State 93 percent Catholic, with Northern Ireland—which remained part of the U.K.—around two-thirds Protestant and one-third Catholic. The Free State, later the Republic, wrote Catholic social policy into law—including banning contraception and divorce—and Church and State cooperated on an entire carceral system for unwed mothers and other accused deviants. In 1922, a group of Protestants were massacred in Cork, Ireland’s southernmost county, shortly after the end of the War of Independence. Even when not subject to violence, Protestant populations in the south declined: in 1911, the combined Church of Ireland, Methodist, and Presbyterian population in the future Republic was over 300,000—almost 10 percent of the total population—and by 1991, it was just over 107,400, about three percent of the total. The 1937 Constitution of the Republic of Ireland recognized the Catholic Church as having a “special position” in Irish society, falling short of declaring Catholicism the state religion, but not that short. It is hard to imagine the counterfactual of what an all-Ireland state might have been like—whether having a substantial Protestant minority would have tempered the possibility of “Rome Rule” or just thrown a bigger minority population under the bus. But unionist fear of an Irish planet was underpinned by some genuine survival instinct, not just irrational hatred.

In Northern Ireland, the Protestant majority oppressed the Catholic minority. James Craig, Northern Ireland’s first prime minister, boasted of the North having “a Protestant parliament for a Protestant people.” The police force—the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)—was almost entirely Protestant, and known for its discrimination, over-policing, and brutality towards the Catholic minority. The “B-Specials” reserve constabulary was entirely Protestant, frequently consisting of state-approved versions of UVF militias. Catholics were systematically discriminated against in housing, employment, and voting: Northern Ireland maintained the property qualification to vote when it was abolished in mainland Britain, disproportionately disenfranchising Catholics, and extensive gerrymandering meant that even nationalist-majority areas were represented by unionist politicians. Basil Brooke, Northern Ireland’s third prime minister, publicly stated that if unionists “allow Roman Catholics to work on our farms we are traitors to Ulster,” imploring them “wherever possible, to employ good Protestant lads and lassies.”

Unionist dominance was absolute. And yet, it simultaneously remained precarious. Though unionists consider themselves British, mainland Brits don’t necessarily see them that way: when Kenneth Branagh, a little working-class Protestant boy raised in such a unionist stronghold in Belfast that he supports Linfield F.C. and Glasgow Rangers, moved to England to escape the Troubles, he self-consciously adopted an English Received Pronunciation accent to avoid anti-Irish bullying. At the start of the Second World War, Winston Churchill offered to hand over the North in exchange for Ireland joining the war on the Allied side. He didn’t ask anybody in Northern Ireland how they might feel about that. Unionists might be British, but that doesn’t mean they could trust the British government to have their backs.

In the unionist mentality, they were constantly under siege: just like they’d been under siege in Derry during the war between the Protestant King William of Orange and his Catholic father-in-law King James II, when thirteen apprentice boys shouted “no surrender!” and closed the gates against the encroaching Catholic forces. I say this not to absolve Northern Irish governments of their abuse, belittlement and violence against Catholic citizens, but to try to understand the why. Holding both in your mind simultaneously is how you approach some kind of moral clarity. By the same token, it is at once true that South African apartheid was an unconscionable evil and that its emergence cannot be fully understood without knowing that a few decades earlier, the British put Afrikaners in concentration camps. And we can condemn Israeli war crimes while realizing that it is impossible to understand the Israeli state’s actions without the context of the Holocaust. As Joe Brolly puts it in an episode of his podcast Free State, after World War II, the Jews who moved to Israel wanted nobody to fuck with them ever again.

Nationalists—and more than that, Irish-Americans and leftists from other countries—can tend to view unionists in two ways, contradictorily yet sometimes simultaneously. Unionists, in this mindset, are Irish people afflicted with false consciousness, tricked into identifying with our British oppressors, and/or Brits who can just go “home” to England, a country they may have never even visited. It’s an attitude that reinforces unionist fears, one that makes it seem rational to think that nationalists would want to extinguish them entirely. That makes it seem good sense to try to extinguish nationalists first.

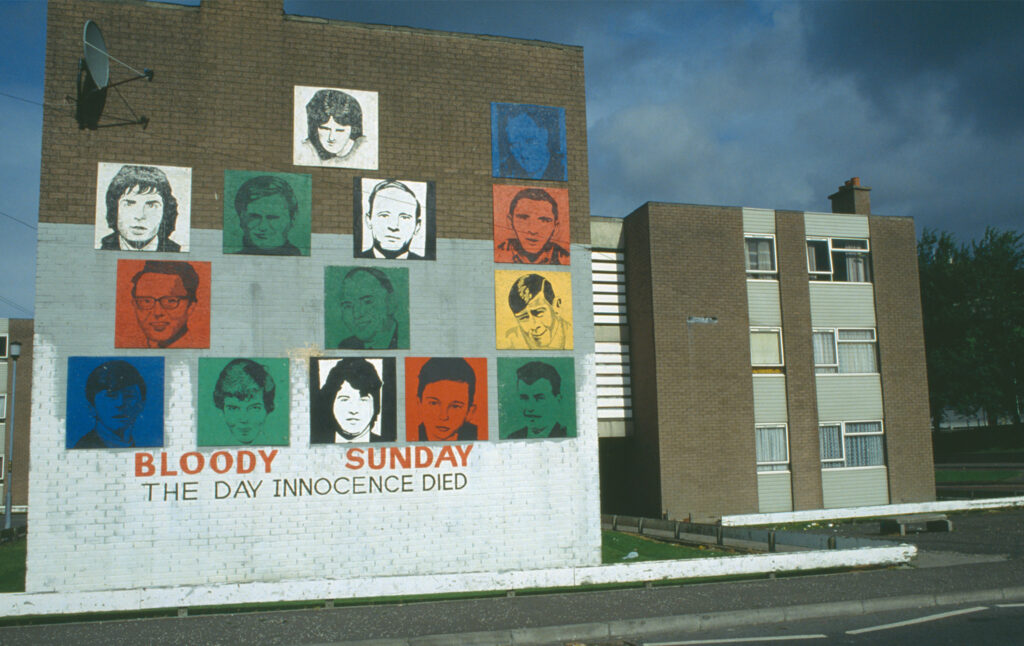

By the 1960s, a generation of young Catholics (and their left-wing Protestant allies) developed a civil rights movement in Northern Ireland, inspired in part by the Black civil rights movements in the U.S. and South Africa. Despite their moderate demands—not for an Ireland united and free, but simply to have the same rights in Belfast and the Bogside as they would have in Bolton or Birmingham—they were met with violent suppression from both paramilitary and state forces. The loyalist paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) petrol-bombed Catholic homes, schools, and businesses. At a civil rights march in Derry on October 5, 1968, the RUC clubbed the protestors with batons, indiscriminately and unprovoked, including beating two Members of Parliament. In 1969, British soldiers were sent into Northern Ireland. Initially, many nationalists welcomed the army as a neutral force, in contrast to the RUC’s open sectarianism, but this didn’t last long. On Bloody Sunday, 1972, British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians at a civil rights march, killing fourteen, as well as injuring more with rubber bullets, batons, and army vehicles. The subsequent tribunal accepted the soldiers’ claims that they were shooting at gunmen and bomb throwers, only going so far as to call some of the shooting “bordering on the reckless.” (A second inquiry found in 2010 that the shootings were “unjustified” and “unjustifiable.” Only one soldier has been charged, and the U.K.’s Conservative government attempted to block his prosecution.)

The violent suppression of the peaceful civil rights movement contributed to the turn towards paramilitary violence on the nationalist side. Bloody Sunday was a flashpoint of recruitment for the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). American leftists—and Irish-Americans of all stripes—tend to romanticize the IRA as a revolutionary organization fighting off colonial oppressors. It’s a simplistic view that blurs and bleeds together often radically different movements, historical and contemporary, into a valorized fight against injustice: one that can justify any brutality. The Washington Post quotes Michael Flannery, the Irish-American organization Noraid’s founder, having said that “the more British soldiers sent home from Ulster in coffins, the better.”

But even if you can justify the IRA’s violence as anti-colonial resistance—and please don’t—it can’t be ignored that the IRA was simultaneously an all-purpose mafia operation: protection rackets, bank stick-ups, prostitution rings, kneecapping, torture, murders without political motivation. Various incarnations of the IRA killed hundreds of civilians. I understand and sympathize with how someone could join the IRA after seeing a British soldier gun down their friends on Bloody Sunday. But I understand it not as a bold action against injustice, but as an act of desperation in a world where there seems to be no other available response to oppression and violence. You tried civil rights protests. You got shot in the street.

What ensued was what seemed like a perpetual tit for tat of atrocities. Some of the most popular historical narratives about war conclude with one side “winning,” defeating the “bad guys” in noble battle. But in the North, as in so many places, war went on with no true prospect of victory or defeat: just a self-perpetuating cycle of brutality and revenge. Violence committed by British state forces or loyalist paramilitaries was responded to with Republican paramilitary bombings, and vice versa. Extraordinary measures to curb Republican violence further restricted the already minimal civil rights of Catholics in Northern Ireland, including the introduction of internment—that is, the arrest without evidence or trial of anyone “suspected” of being involved in the IRA. If certain Irish-Americans financially supported Republican paramilitaries, it must also be remembered that Margaret Thatcher “effectively used girl power by funnelling money to loyalist paramilitary death squads in Northern Ireland.” It was Thatcher’s belief that a military defeat of the IRA was both possible and necessary. Her total unwillingness to make concessions meant hunger strikers, who wanted to be treated as political prisoners, were left to starve to death in prison.

But how do you militarily defeat terrorist organizations? Over two decades into the War on Terror, you’d think we’d have cracked it. But instead, it seems like the War on Terror was a process of systematically forgetting how, exactly, one fights terror. A collective dream that terrorists are not rational actors, are not even human beings: that they are recruited simply because they are evil, and so they need to be put down like dogs. But if you know anything about terrorism, you know that killing the terrorists themselves doesn’t kill the organization. The U.S. spent twenty years fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan, and it ended with the Taliban immediately taking back control of Afghanistan when the U.S. army left.

In Northern Ireland, internment, massacres, and other attempts to defeat the IRA were most effective as IRA recruitment tools. And when the IRA declared a ceasefire and participated in peace talks, it was following peaceful nationalist and civil rights activist John Hume’s decade of secret talks with the IRA at the height of the Troubles. Hume “was singularly against the IRA,” Gerry Adams said on Hume’s death, “but he was a Derry man so he knew that republicans who were involved in armed struggle were serious, so the way to get at that wasn’t to have the stand-off that we had.” It’s a political truism that you can’t negotiate with terrorists. But when the benefits were reaped, John Hume became the only person to ever win a Nobel Peace Prize, the Gandhi Peace Prize, and the Martin Luther King Award. And he was voted Ireland’s greatest-ever person in a 2010 poll by RTÉ, the country’s public broadcaster.

In the endless cycle of tit for tat violence, a post-traumatic state becomes the norm, and hatred becomes rationalized, justified, intellectualized. But hatred isn’t liberatory. It’s confining. It damages your own soul and makes it easier to hurt people around you—to participate in the cycle of violence that hardens more hearts. “One common truth was that the hurt and the pain on both sides was sadly the same,” Patrick Kielty, a comedian and TV presenter whose father was murdered by a loyalist paramilitary group, said. “We all shared something, but we just didn’t realize it at the time. And there were days where we thought it would never end.”

That these cycles of violence can end seems impossible, and impossibly naive. In the current war in the Gaza Strip, even calling for a temporary ceasefire is treated as inappropriately radical by both major parties in the U.S. and U.K. As an Irish leftist, I have been put in the extremely annoying position of having to be grateful for the political and moral courage of our right-wing Taoiseach Leo Varadkar. The position of so many countries seems to be that violence can and will and should go on forever, until one side defeats the other utterly.

In Northern Ireland, according to former Irish Ambassador Bobby McDonagh, both sides came to understand that a military victory was impossible. And if “victory for neither side was possible,” he writes, then “without a peace agreement, at least another generation in Northern Ireland would be condemned to suffer.” And a peace agreement came to be: through a leap of faith, through a willingness to see, to hope, to imagine. To believe that something else is possible, and to be willing to make compromises to get there. After decades of efforts that stalled out or failed, in 1998, we got the Good Friday Agreement. The Irish state removed by referendum a constitutional claim over Northern Ireland, with all parties acknowledging that Northern Ireland would remain a part of the United Kingdom as long as that was the will of the majority of the people of Northern Ireland. Irrespective of any change to constitutional status, the people of Northern Ireland would be entitled to identify as British, Irish, or both. On certain issues, a cross-community vote would be required in the Northern Irish parliament—meaning a majority of both nationalists and unionists. Over 400 prisoners serving sentences for paramilitary activity on both sides were released. The RUC was replaced by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), which moved away from the militarism of the RUC toward community policing and implemented affirmative action to recruit more officers from a Catholic background. Paramilitaries on both sides committed to decommissioning their weapons—and even though, like so much in this ever-imperfect peace, it took longer than was planned, those weapons were decommissioned.

But because the cycle of violence is self-perpetuating—because every atrocity demands an atrocity in return—it’s the duty of the international community to create the space for that leap of faith. To knock some heads together until empathy leaks through. It’s taken as a given that the international community can underwrite war and atrocities, but the other side of that coin is an ability to underwrite peace, stability and justice. But it takes active, difficult work. Even leaving aside actual illegal activities, like funding paramilitary groups, international priorities have not always reflected what would benefit the peace process. British Prime Minister Ted Heath pulled Willie Whitelaw out of his role as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland right as an attempt at power-sharing was being set up in the 1970s, because since he was such a good negotiator, he wanted him to deal with the miners’ strike back in England. (Five decades later, Northern Ireland seemed to hardly be a consideration when the U.K. voted to leave the European Union. Dominic Raab, the Brexit minister, admitted to never reading the Good Friday Agreement in its entirety—mind you, it’s only 34 pages long, including the title page and table of contents.) Tony Blair later turned out to be a warmonger, but in the 1990s, he played a pivotal role in the Northern Ireland peace process. Mo Mowlam, Blair’s secretary of state for Northern Ireland, kept her brain tumor a secret out of her dedication to working on the Good Friday Agreement. Taoiseach Bertie Ahern helicoptered between Belfast and Dublin to be able to participate in the talks and attend his mother’s funeral. Bill Clinton allowed the U.S. to function as a neutral broker and appointed George Mitchell as United States Special Envoy for Northern Ireland, in which role he co-chaired the negotiations. A decade later, militant unionist Ian Paisley and former IRA man Martin McGuinness were getting along so well that the press nicknamed them the Chuckle Brothers.

In the final episode of Derry Girls, a sitcom set during the Troubles, our teenage protagonist has to decide how to vote on the Good Friday Agreement: the document that we, the viewers, know will be the foundation of the peace process. “What if we do it, and it was all for nothing?” she asks her grandfather, worried in particular about the promised release of prisoners. “What if we vote yes, and it doesn’t even work?”

“And what if it does?” her grandfather answers. “What if no one else has to die? What if all this becomes a ghost story you’ll tell your wains one day?.… A ghost story they’ll hardly believe.”

Grandpa Joe was right. And that’s all I dream of—that one day all of this will be a ghost story our kids will hardly believe.

If yoou want to take much ftom this pos ten you have to

apply tbese strategies to yokur wonn weeb site.