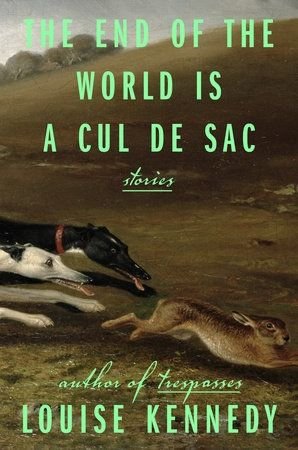

While some of today’s entertainment can seem like an unrelenting series of traumas, Louise Kennedy’s approach to the roots of suffering is a refreshing change.

The protagonists in her live-in collection, The End of the World is a Cul-de-Sac, all suffer, but with a few exceptions, nothing too extraordinary befalls them. That is not to diminish the real pain or the (sometimes aggressive) forces organized against these women and girls. It simply observes that the things they deal with, react to, and are consumed by are not as exotic as illness, aging, relationships, parenting, mental health issues – the problems of life. only.

Through 15 stories set in the small towns and countryside of northern Ireland, Kennedy trains a breathtaking scrutiny into the people of his subjects: their homes, their communities, their skins. These are lives in progress, enhanced by imaginative backstories that immerse us in the lead-up to key moments and stages.

In the title story, Sarah’s husband runs away, burdened with debts. As the stray donkey wreaks further havoc, she receives assistance from her neighbor, whose motives are far from altruistic. In “Imbolc”, Elaine also overcomes the aftermath of her husband’s misdeeds, and at the same time her own body, which has not yet recovered from the birth of her daughter, becomes “huge” again and “a new body with a purple lace pattern” I’m watching her develop “stretch mark stripes.” She on both sides of her diaphragm. ”

The husband is just one potential source of danger. After Eain’s American boyfriend, Ethan, dies, in Powder, she is quickly “cast as a tragic young fiancée” who takes her grieving mother to find her ashes in the Irish countryside. I was ordered to lead him to scatter his ashes. However, even though she told Ethan that he was going to propose to her parents, she never actually proposed. Although Eisne misses her chance to come clean and she ends up being complicit in “the secrets people kept, the lies they told,” this couplet may serve as an epigraph to this collection. do not have.

Teenage Roisine in “Belladonna” worries that Oliver harbors a secret that might endanger not only the time he spends helping his wife Anna run her herbal clinic, but also Anna herself. are doing. And in her yearning, hopeful “Brittle Things,” Ciara takes her 5-year-old son, who has never spoken to, hugged or kissed her parents, to speech therapy. But she hasn’t told her husband about it yet. This is because her husband’s concerns at home come second to concentrating on work.

Kennedy listens for the beauty of words, such as the metrically primitive “Anna is tapping the primroses in the pot on the porch.” And she pays close attention to her characters’ regional accents and rhythmic nuances, occasionally translating them into “Not at all, he says. It’s not that expensive,” he even wrote.

Many women suffer in silence, out of exhaustion and resignation rather than weakness. But Mairead in “Sparing the Heather” is different. She enjoys both her husband and her lover, the man who rents her property, which leads to a subtly electric ending. Kennedy packs her life into these stories, but I love her entire novel about Mairead’s future, as well as several other novels she introduces in these captivating tales. welcome.